Austin Kelly staged a daring escape from German lines in France in 1917. Photo: Chris Roe.

The 1963 American war adventure film The Great Escape has nothing on Wagga Wagga teenager Austin Kelly’s dramas and getaway on the Western Front in World War I.

Private Kelly’s remarkable deeds are fully told in my 13th annual Riverina Anzac booklet, but for Region readers, here is a special insight into a remarkable boy and his extraordinary feats.

They say truth trumps fiction and this may certainly be the case with Wagga Wagga World War I digger Austin Kelly – who lied about his age so he could go to war. Austin was a mere 15 years young when he enlisted to fight and his attestation papers went as far as to describe his complexion as “fresh”!

Austin Kelly was born in Wagga Wagga on 27 November, 1899, the youngest son and middle child of well-known and highly respected local drover James Patrick Kelly and his wife Isabella Susan Marion (nee Donnelly).

Older brother Leo was not quite two when Austin arrived and the Kellys would add a daughter, Mona Maria, in 1904.

Both boys were educated by the Christian Brothers and would enlist at a young age; Leo aged 18 years and a month and Austin just 15 years and eight months even though he signed his attestation papers to say he was 21 years and a month.

Leo Kelly was the first to join up and did not come home from the Western Front. Photo: Australian War Memorial (enhanced).

Leo answered his country’s call on 23 March, 1915; Austin later the same year, on 30 July. Interestingly, members of the Australian Imperial Force had to be at least 19 when Leo joined but his father gave consent to allow him to go to war. Heartbreakingly, James Kelly would never again see his boys once they set off for the war.

Leo Kelly joined the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force at Gallipoli on 16 August, 1915, remaining on the ill-fated peninsula until the end of the campaign.

On 18 March, 1916, Leo was part of the British Expeditionary Force sent to the Western Front. Sadly, four months after he disembarked at Marseilles, Leo went missing in action.

Tragic confirmation of his death came in a statement made nearly 13 months after Leo disappeared. On 26 September, 1917, Mr Kelly was given the news no parent ever wanted to hear.

On the morning of the day he was killed, Leo wrote to his father more than 16,700 kilometres away in Wagga Wagga and his closing words were: “Whatever happens I am satisfied. We have been through a rough time for 19 months, but everyone has treated me well, and I face the future contented.”

Leo was exhumed and reinterred in Pozieres British Cemetery. “God remembers when the world forgets” is the inscription chiselled into his white marble headstone over grave 12, plot 3, row O.

Austin Kelly survived WWI and signed up for WWII. Photo: Supplied (enhanced).

Austin Kelly was very young when he left school and described himself as “not a very good scholar”. He stated on his enlistment papers he was a labourer who worked on the railways “for a while” after leaving school.

Enlisting in Melbourne, Austin steamed out of Melbourne aboard HMAT Ceramic A40 on 23 November, 1915, with the 4th Light Horse Regiment.

Austin had an eventful war and was fortunate to have one last catch-up with his brother in Suez.

He was captured by the Germans in France and, as a prisoner of war, had been compelled to act as orderly to a German officer – a life of slavery, badly fed, and poorly clad.

It was during 1917 that Austin staged a bold and miraculous escape, which he wrote home about, and the story was published in Wagga’s Advertiser.

One day the German officer he was serving galloped to his quarters, jumped from the saddle and threw the bridle to Pte Kelly. Within an instant, the quick-thinking private was in the saddle, galloping for his life towards the British lines.

The officer’s revolver was in the saddle flap, so he could not fire at the escaping Australian.

With darkness coming on, Kelly was comparatively safe but he had nearly 65 kilometres to ride to the British lines.

“The time was opportune, as a terrific fight was in progress and a galloping horse was no novelty,” Pte Kelly said in his letter.

He was offered furlough on his return, but preferred to have, as he reportedly put it, “another go at the Huns”.

Whether entirely true or not, it makes for riveting reading and, importantly, no-one at the time doubted its veracity.

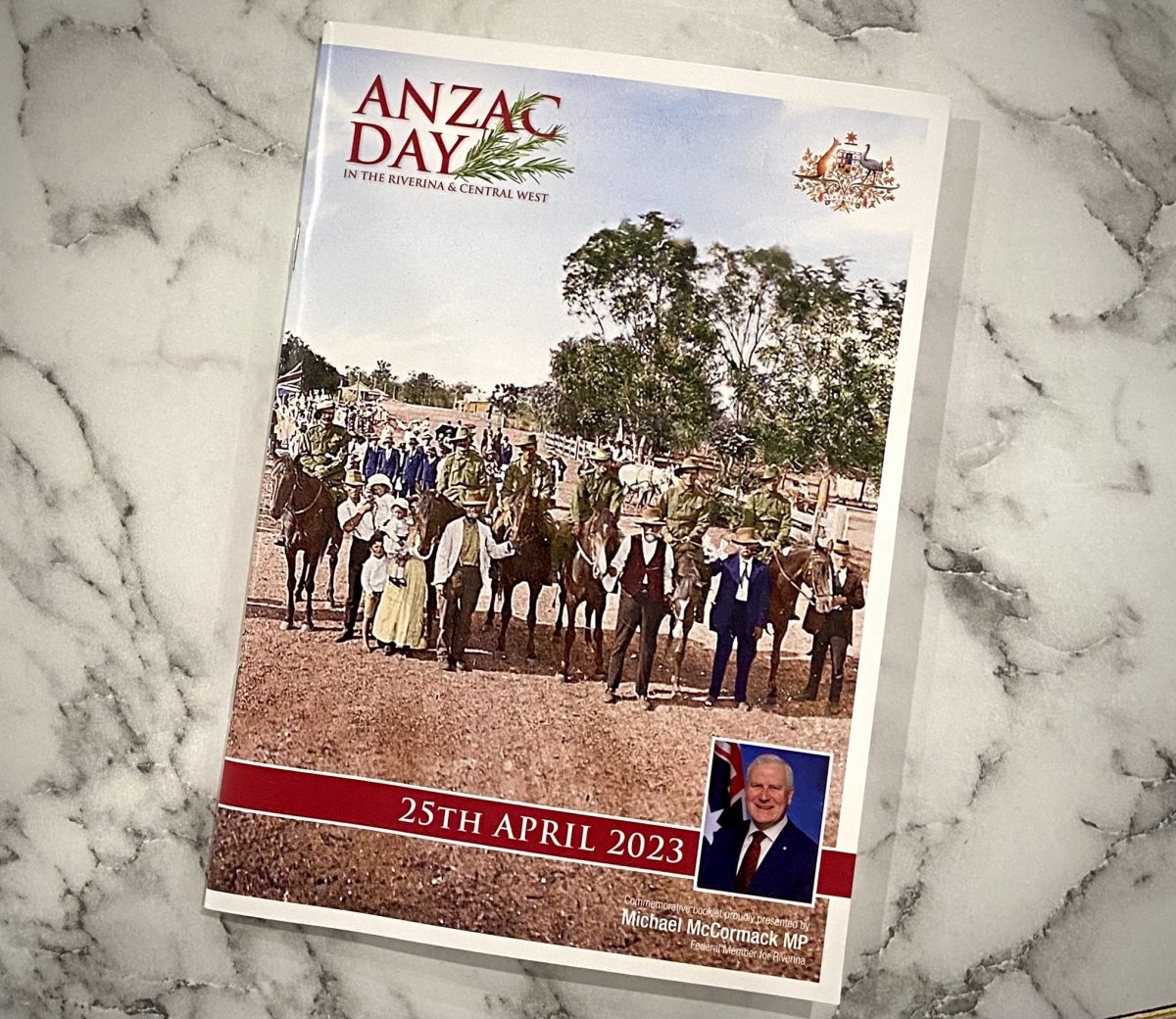

The Kelly brothers’ story is one of many in Michael McCormack’s 13th annual Riverina Anzac booklet. Photo: Chris Roe.

What we do know is on 30 September, 1917, Austin was wounded in action in France, sustaining facial gunshot wounds as well as to his left arm, which was fractured, as was his right leg.

Once he was stabilised, Austin was taken to England to recover before returning to the front as a gunner, posted to the Australian Field Artillery 17th Battery on 9 March, 1918 – the very day he fell victim to gas poisoning. Austin’s fighting was finished – at least in this war.

Boarding HT Essex on 7 June, 1918, he sailed for home, his papers stating his gunshot wound to his left arm had caused a partial loss of his elbow.

By the time Austin arrived back in Wagga Wagga, he was still only 17 and a half years of age, not old enough even then to be eligible to enlist.

By the time he made it home, his father, James Kelly, had passed away, aged 50.

Leo Kelly’s name is on Wagga Wagga’s Cenotaph. Photo: Supplied.

Austin had experienced an action-packed two years of close shaves, painful direct hits and escapades and had been extremely lucky to live to tell the tale.

But he was not done yet.

He presented himself at Paddington on 24 October, 1941, to serve in World War II, and at least this time he did not have to fabricate his age.

He did not serve for long – only until 23 January, 1942 – but he put his name forward at a time when our nation was in grave peril.

Austin would spend his final years in Lawson in the Blue Mountains, passing away on 14 May, 1969, aged 69.

The Kellys are immortalised on Wagga Wagga’s magnificent sandstone Memorial Arch, opened on Anzac Day 1927.

One thing we know about the Kelly boys is that they gave their all for the cause and, as a country and community, we can be thankful we had volunteers with their get-up-and-go when it mattered most.

Michael McCormack is the Federal Member for Riverina and Shadow Minister for International Development and the Pacific.