Albury landscape artist Nat Ward at home in her studio … the 58-year-old has won the 2025 John Villiers Outback Art Prize. Photos: Supplied.

When Nat Ward learned she had been awarded her first major national art prize, she admits “I got a little bit overexcited”.

The Albury landscape artist found out at 9:30 pm on a Saturday that she had won the 2025 John Villiers Outback Art Prize with her painting Beautiful Scrubland.

“It was just as I was going to bed,” the 58-year-old says.

“I lay there and couldn’t sleep – so I went into the studio and painted for two hours.”

Indeed, she laughingly reflects, that’s probably what it means to be completely absorbed by your craft.

“If I wasn’t an artist, I’d probably go mad,” she admits.

Ward, who has been a finalist in numerous prestigious art prizes and held successful solo exhibitions in Sydney, Melbourne and Albury, says it’s amazing to even be a finalist in any of these competitions.

“But to actually win, well … this is it!”

This year’s John Villiers Outback Art Prize, an annual competition open to all Australian artists, attracted more than 300 entries and a shortlist of 40 finalists for the $10,000 first prize.

Artworks in the competition, which is presented by the Outback Regional Gallery and the Waltzing Matilda Centre at Winton, in Queensland, must correspond to the theme: ”Outback: A Sense of Place”.

Ward admits she tends to “wing these things” but was “pretty happy” with the finished 130 cm x 100 cm painting she submitted.

“I’m pretty hard on myself in terms of making sure it was a finished piece,” she says.

“Some people go for the big, wow landscapes whereas I like to go for something more subtle that might sometimes be overlooked.

“Scrubland is not necessarily that pretty but if you look closely, there are interesting nuances, colours and patterns.”

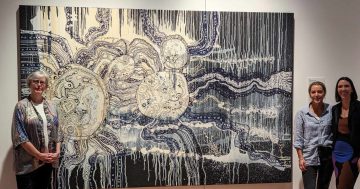

Nat Ward’s Beautiful Scrubland contains interesting nuances, colours and patterns, she says.

Ward – who has been painting “for forever” – always knew she wanted to be an artist.

“I knew from when I was very little, like five years old,” she says.

“I know it sounds cringeworthy, but I used to have this feeling I could do it. It’s like a little kid who can sing, I always knew I was good at it.”

Born in New Zealand, Ward gained a Fine Arts degree majoring in painting from Canterbury University.

After a stint working in the commercial art sector, she has devoted herself to being an artist from her home in Albury, where she spends her days hiking in the nearby hills, exploring high-country trails, and swimming in the Murray River.

And while she loathes the word “inspiration”, she draws her influences from the breathtaking landscapes of Albury, including the natural bushland of Nail Can Hill and the mighty Murray.

“I walk up there a lot – it’s part of our psyche around here,” she says of the iconic ‘Nail Can’, around which she is basing a current body of work.

“It’s really bloody hard to be an artist.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re in the city or the country, it’s hard to get into good galleries who value what you do.”

From the cost of paint (a small tube of quality paint can cost $80) to paying for entries to art competitions (and the associated costs of framing and mailing your work), it’s a tough gig, according to this once-struggling artist.

“You paint and then hope somebody is going to like it and buy it,” she says.

While she has a few of her own paintings hanging in her house, Ward says, “I’m not super attached to anything”.

“I’m happy to do a good job and pass it on to someone else to enjoy.”

Many of Ward’s paintings hang in private collections and even lawyers’ chambers, but she is still proudest of the two exhibitions held in her hometown at MAMA (Murray Art Museum Albury), the latest a project that explored the connections between Albury’s riverside park and its namesake in France.

The 2024 Noreuil exhibition was the culmination of a two-year project bringing together the shared history of Noreuil Park and the French village, where a group of Albury soldiers would bravely fight in a pivotal WWI battle.

Ward, who visited the tiny village in France as part of her research, describes the project and resulting works as a “profound journey” that deepened community awareness and celebrated the enduring bonds between two distant yet intrinsically linked places.

To learn more about Nat Ward’s work, visit her website.