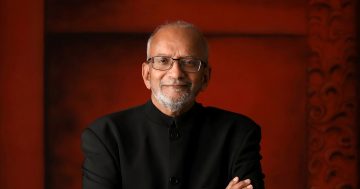

Dr Stuart Gamble with an engraving from “A System of the Anatomy of the Human Body”. Photo: Chris Roe.

Content warning: This story contains images which may distress some readers.

Vascular surgeon Dr Stuart Gamble has practised for more than 48 years, spending the latter half of his career in Wagga.

“My primary concern is to care for the patient to the best of my ability,” he reflected over a cup of tea in his Wagga townhouse.

Born and bred in the bush, Stuart said he was motivated in life by his faith and family and returned to work in regional Australia to find a more balanced lifestyle.

“I’m not defined by being a surgeon,” he said. “I’m a Christian first. My wife is my most important priority and then my family.”

He said his vocation had been both a privilege and a responsibility.

“I’ve tried to divorce the business side as much as I can so that it doesn’t influence any of my decisions in terms of how I treat patients or who I see,” he said.

“You need to see it as an opportunity to serve.”

The youngest son of a farming family from Colbinabbin in central Victoria, Stuart was lured off the farm in his final year of high school after doing work experience with both a vet and a local GP.

“I decided I didn’t want to be a farmer,” he said.

Stuart enrolled in medicine at Monash University where he met his wife Carole who was studying biochemistry.

After three years on hospital training campuses, he became a resident at the Queen Victoria Hospital in Melbourne, a uniquely progressive institution primarily run by women.

“Victoria Hospital was established around 1900 because women couldn’t get hospital postgraduate training – particularly in the specialties,” he explained.

“They built the Queen Victoria Hospital because the first female graduates could not get a residency.”

Stuart says it was a privilege to serve under some notable female pioneers who continued to face prejudice in the 1970s.

“In my first year out I worked with Lorna Sisely who was the first female surgeon that did all her training in Australia, and also Joyce Daws who was made a Dame of the Empire and was the first thoracic surgeon in Australia,” he said.

With the support of these feminist icons, Stuart spent a decade training to become a surgeon in Melbourne and the UK.

Dr Gamble at work using an abdominal Omni-tract retractor. Photo: Stuart Gamble.

Always a country lad at heart, he and Carole packed up their four children and moved to Tamworth in 1984 where he would practice for the next 14 years.

“I deliberately went to the country because I wanted to be able to spend more time with my children as they grew up,” he said.

As the children began drifting south to Melbourne for study, the family settled on Wagga as a closer regional alternative.

“I joined Graham Richardson’s practice in Wagga,” Stuart said.

“He was also an associate professor and helped set up the first rural medical school in Australia here (UNSW Rural Clinical Campus).”

He said many young doctors who trained in Wagga have enjoyed the lifestyle and have either returned or taken up other regional positions.

“We’ve always done the surgery well but in some ways, our city colleagues have been our worst enemy,” he said.

“They try and give the impression that there’s no point having anything done in the country because you won’t get it done as well.

“But when we publish our results we are as good or better than inner-city units.”

Stuart said recruiting doctors to work in the regions remained an issue with most medical students choosing to stay in the cities.

He believes that more needs to be done to actively target students from regional backgrounds who are more likely to return.

“You prioritise people with a rural background getting into medical school and then you prioritise rural people getting into the specialty training programs,” he explained.

“It’s the same with Aboriginal and Indigenous students as well; they are grossly underrepresented.”

Recruiting from overseas has become the go-to solution for Australia’s shortage of rural doctors.

While Stuart said many are excellent clinicians and the system would not survive without them, he questioned the ethics of poaching trained physicians from other countries rather than training our own.

“It would be preferable not to remove them from their own countries and instead to do whatever it takes to make sure we’ve got local Australian graduates,” he explained.

“I think it’s an ethical issue and it means that Australia has gotten by without putting the money and the hard work into having adequate medical schools for many, many years.

“They’ve just pinched them from overseas.”

In his 38 years as a rural surgeon, Stuart practised general, breast, vascular, burns, paediatric and skin cancer surgery.

He said he had seen tremendous changes in surgical techniques and equipment to develop ‘minimal access’ surgical approaches and vascular surgery developing as a separate surgical specialty.

His advice for the next generation is simple.

“Come to the country,” he smiles.

“Make sure you’re within half a day’s drive of your extended family.

“There are terrific facilities and you’ll have no end of work – you have an instant practice when you come.”