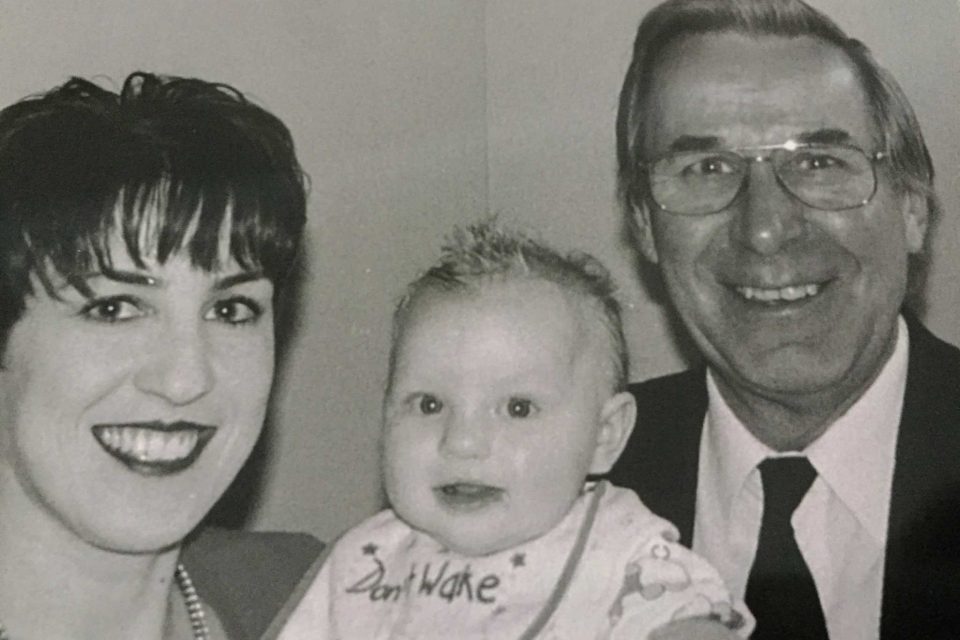

Cindy Flint with her daughter Lucia, who was born with a cleft lip and palate, and her son Riley. Photo: Supplied.

When Cindy Flint’s daughter Lucia was born with a cleft lip and palate, she was asked if she had been given the option of having an abortion.

Tears well up in the mother of two’s eyes as she says it wasn’t something she would have ever considered.

“Look at what we, and the world, would have missed out on,” Cindy says looking towards her daughter, now 21, as they share their story across the dining table.

“She’s a blessing and a gift.”

Cindy found out at her 18-21 weeks ultrasound her daughter had a cleft lip and the cleft palate was confirmed at birth.

“I took folic acid tablets, there was no family history of this genetic issue that they class as a birth defect. It was new to me,” she explains.

“As a mother, I felt I had burdened my child with something and it was out of my control … it was a difficult mental adjustment because we knew it would be an unpredictable journey.”

Lucia’s paediatrician told Cindy to ‘think of the worst and hope for the best’.

“A co-worker said to me — ‘You want to hope it’s a male so it can grow a moustache’,” she recalls.

“Those words don’t help the healing process. They just hurt. It’s of no comfort to anyone when they’re dealing with an issue.”

Lucia listens with frustration as Cindy describes the way people responded to news of her condition.

“What am I meant to take from that? Am I defective? As a young person that’s hard to hear and to hear that what you have is classed as a ‘birth defect’,” she says.

Lucia hopes for a change in the language that labels people as defective or deformed.

“It’s considered as a birth defect, malformation or deformity. I’ve had conversations in my speech journey about the need to rewrite the language,” Lucia says.

“These are facial differences. Everybody has a different face. There should be no expectation about what someone should look like or ‘a typical baby’.”

Lucia has undergone about 10 surgeries since birth and she has seen an orthodontist since she was two weeks old.

At 12 she had a bone graft and at 15 she was given options for cosmetic surgery to alter the structure of her face but chose not to pursue them.

“I got my face measured on both sides to asses my facial symmetry … I was told I have an overbite and underbite at the same time,” Lucia says.

“I was very adamant about my decision to not get that done – and that’s not to say other people shouldn’t do it – because everyone needs to do what’s right for them.

“I don’t want young people to get surgeries done to feel like they’re ‘worthy’ or look ‘right’.”

Lucia is pursuing speech pathology and hopes to continue advocating for young children born with cleft lip and palate. Photo: Shri Gayathirie Rajen.

While she’s had the support of her family and her best friend, Lucia says that there were moments when people said things that unintentionally hurt her.

As a teenager, she felt undesirable but says that as she grew older, she understood that authentic relationships were more than skin deep.

“My purpose in life is not to be a wife, desired by a man … I have a greater purpose. I have goals and aspirations.”

Lucia and Cindy Flint are hoping to raise awareness of and remove the stigma around the condition. Photo: Shri Gayathirie Rajen.

Lucia is studying to become a speech pathologist and hopes to work with and encourage young children with the condition.

Fighting back tears, she says she will tell them, “It’s going to be OK”.

“That’s all I wanted when I was little … someone to say it’s really hard but you’re going to be OK,” she says as the tears roll down her cheeks.

July is Cleft and Craniofacial Awareness Month and both mother and daughter are hoping to raise awareness of and remove the stigma around a condition that affects one in 700 children.

They hope that creating more understanding of the condition will help parents and caregivers to work through their fears as they face the challenges of a long journey through the medical system.