November and December have been far wetter than typical El Niño years. Photo: Resilience NSW.

While nobody can deny that extreme weather is part of how the world works and always has been, if we take a snapshot of just the past few years, it’s pretty clear that Australia has probably had more than its fair share of catastrophic events in that short time – whether they be naturally occurring, or have been triggered or amplified by climate change.

The catastrophic 2019/2020 Black Summer bushfires in eastern Australia were the worst on record and came at the end of a long period of drought.

There was also extensive flooding in northern Victoria in 2021, the NSW north coast twice in 2022, Brisbane and areas of southeast Queensland in 2022, the lower reaches of the Murray River in 2022-23, the Kimberley region of Western Australia in early 2023 and just last month far north Queensland was inundated by floods caused by ex-Tropical Cyclone Jasper.

After three summers of a La Niña weather pattern to which the floods were largely attributed, we were told the reverse El Niño pattern would establish itself over Australia by spring, bringing hotter and drier conditions.

El Niño – Spanish for ‘the boy child’ – occurs when the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific become warmer than average. This leads to a shift in rainfall away from the western Pacific and eastern Australia toward the central and eastern Pacific. Australia last experienced an El Niño event in 2016-17, and then again in 2018-19, with 2019 being Australia’s then hottest and driest year on record.

Conversely, La Niña – or ‘the girl child’ – occurs when equatorial trade winds alter Pacific surface currents and bring cooler deep water up from below. This has a cooling effect on the central and eastern Pacific while warmer waters are drawn to the western Pacific, resulting in increased rainfall over northern and eastern Australia. La Niña took hold at the end of 2020 and continued through three consecutive summers to 2022-23.

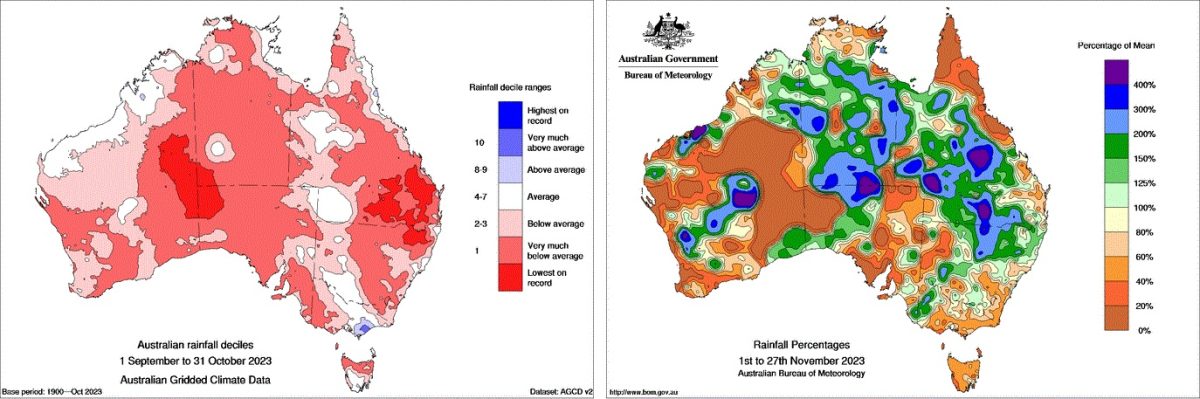

While September and October 2023 were typical of an El Niño and were, according to Weatherzone Business, the driest two-month period since 1900, the wet weather returned in November.

While these events are still relatively cyclic in nature, studies show they are not only becoming more frequent but also more intense. When combined with Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) events – the Indian Ocean’s equivalent of El Niño/La Niña – they can have a continent-wide effect.

During the positive phase of the IOD, the eastern Indian Ocean experiences lower-than-normal sea-surface temperatures – the warmer waters in the west cause more rain over Africa, and there is less rainfall in Australia. During the negative phase of the IOD, these conditions are reversed and Australia is cooler and wetter.

Charts show the lack of rainfall across Australia in September and October (left), compared to November (right) when above-average falls were experienced across the continent. November’s pattern extended right through December. Images: BOM.

Weatherzone Business points out that “no two El Niño events impact Australia in the same way” and that other factors such as jet streams can influence individual weather systems.

The CSIRO says that during the three consecutive La Niña years of 2020-23, heat had built up in the equatorial Pacific Ocean, which in turn relaxed the trade winds, thus triggering an El Niño event.

But it adds that increasing ocean surface temperatures attributed to climate change mean a typical La Niña year now is warmer than El Niño years were 30-40 years ago. It further says that these events are “likely to increase in amplitude and frequency due to climate change, having stronger effects and occurring more often”, resulting in more flooding in some Pacific Island nations and more drought on mainland Australia.

On top of that, the CSIRO says extreme positive IOD events are also likely to increase as the climate changes and, when they correspond with El Niño events, will bring more drought to Australia.

It appears that climate change has effectively meant the models the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) use to forecast weather events have been left behind.

In the wake of the storms in southeast Queensland over the Christmas break, local councils complained that they had received little or no warning from the BOM about the severity of the event.

In an interview with the ABC on 30 December, Federal Minister for Emergency Management Murray Watt acknowledged the criticism.

“There’s obviously been a lot of criticism of the [BOM] in recent days, and I’m very open to the view that we can do better with the BOM and I’m sure that work will go on there.

“But I think the other thing we do need to recognise … is that climate change is having an impact,” he said.

“It’s having an impact in terms of more frequent disasters, more extreme disasters, and that provides some difficulties for the BOM as well.

“The models that we’ve traditionally used are having to change because the climate is changing. That’s something that I know the BOM is working hard on, but unfortunately, the reality is that climate change means that we are going to be living through more unpredictable weather.”

Original Article published by Andrew McLaughlin on Riotact.