Griffith student Emily Vasta says it’s hard for her to travel back home. Photo: Raiya Gyles.

University students from Griffith are calling for ongoing government financial assistance while they complete their degrees, highlighting huge disadvantages for country school leavers compared with their city counterparts.

Eligibility for the main federal government financial support payment for university students aged under 22, the Youth Allowance, is determined by parental income, even if the student is an adult and living independently away from their parents’ home.

This means if the parents’ combined income is above a certain level, rural students – most of whom have to move away to pursue tertiary studies – can be left with no government support at all.

Imreet Singh, 18, who moved from Griffith (a town with no university) to Sydney to study medicine at the University of NSW this year, said the system was unfair.

“If it weren’t for my parents’ support, I wouldn’t be able to go to university,” Mr Singh said.

“It costs $20,000 per year to live at University of NSW, plus $5,000 set up costs to pay for laptops and textbooks etc.

“I’ve received a couple [of one-off payments], but nowhere near enough to cover all my expenses for the year.”

Mr Singh said it’s harsh to cut students off from ongoing financial simply based on their parental income, especially since some parents may be unwilling or unable to financially support adult children living in an expensive big city like Sydney.

Medical student Imreet Singh. Photo: Oliver Jacques.

One Griffith single mother Region Riverina spoke to said she only works part-time and refuses full-time job offers to keep her income low enough to enable her child to be eligible for government assistance.

“There needs to be some sort of agreement whereby Government provides more ongoing support [for rural students living away from home],” Mr Singh said.

Griffith’s Emily Vasta, 20, a second-year occupational therapy student at Charles Sturt University in Albury, agreed.

“I get very little assistance,” she said.

“In my first year, I applied for eight scholarships but didn’t get any of them.”

Ms Vasta said that in a bizarre paradox, many scholarships are only eligible to those who already receive government assistance.

“That means I’m left with nothing,” she said.

“It’s very stressful. I can’t afford to eat red meat; we usually eat chicken or vegetarian dishes. I also can’t come home to Griffith as much as I like, because of the cost of petrol.”

Ms Vasta did get a grant from the Country Education Foundation, a not-for-profit group that uses donations to financially support rural students living away from home. But she said it only got her through her first eight weeks.

She said she worked part-time and sold her artwork on Instagram to help pay the bills, but it was tough to balance this with intensive full-time course work.

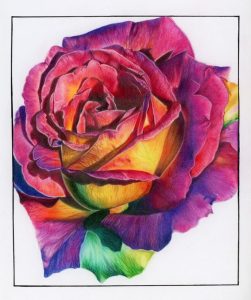

Emily Vasta’s art. Photo: Supplied.

“As part of my degree, I also have to do an unpaid internship, which leaves little time for paid work,” she said.

When Region Riverina raised these concerns with the Federal Government’s Department of Social Services, which administers the Youth Allowance, a spokesperson said:

“Youth Allowance is based on the principle that financial support for students is a shared responsibility between parents, the Government and students themselves … eligibility for Youth Allowance reflects the expectation that, where they are able, parents should support dependent young people in their care until they achieve financial independence.”

The Griffith students Region Riverina spoke to argued that adult university students living hundreds of kilometres away from home are not in the care of their parents and that it is unfair to base Youth Allowance on parents’ willingness or capacity to give them money.

Mr Singh added the current system placed rural university at a huge disadvantage in comparison to their city counterparts.

“Most of my uni friends who are from Sydney still live at home with their parents, so they face nowhere near as many expenses as us,” he said.