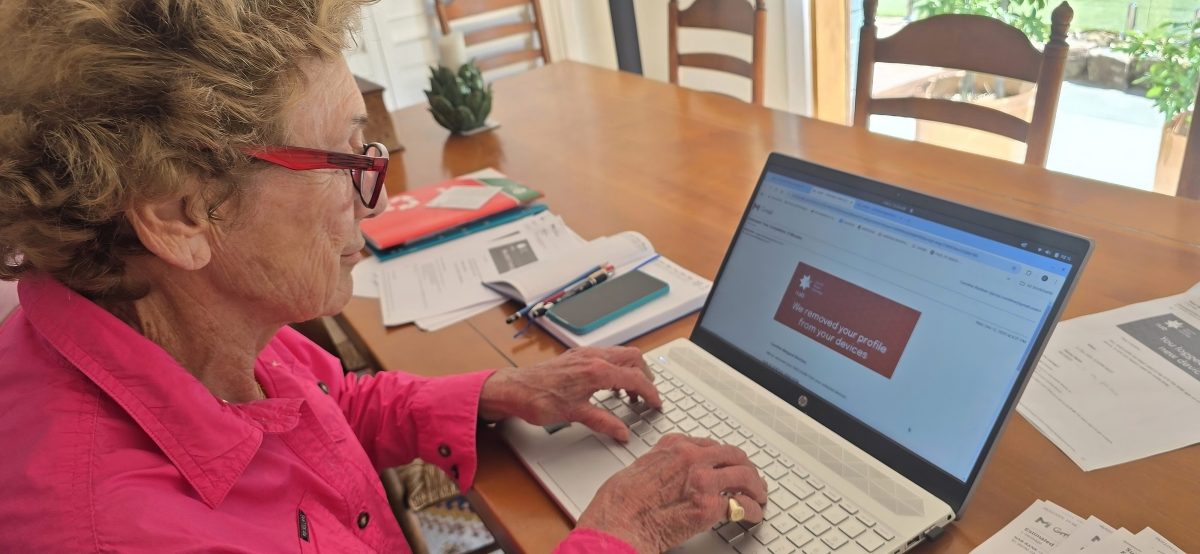

Caroline Buchan lost $34,000 after an alleged fraud. Photo: Shri Rajen Gayathirie.

Year in Review: Region is revisiting some of the best Opinion articles of 2025. Here’s what got you talking, got you angry and got you thinking. Today, Oliver Jacques goes in to bat for victims of scams.

“How people fall for this is beyond me,” was a comment typical of many on social media when Region reported on one of two women who lost money to scams last week.

But rather than judging victims without knowing all the facts, we’d be better off showing them support and sympathy while holding powerful institutions that fail to protect the vulnerable to account.

Caroline Buchan is an 80-year-old who went to her National Australia Bank (NAB) branch, where NAB fraud squad officials re-activated a credit card the bank blocked while she was overseas.

Soon after leaving the bank, a person identifying herself as an NAB fraud squad official (who somehow knew her NAB customer number) told her she needed to transfer money out of her account. She also received emails with the NAB logo telling her to do the same.

After losing $34,000 to this elaborate ruse, she appealed to her bank to recover this money. NAB said they couldn’t do that and instead suggested she call a suicide prevention service.

You would think this traumatising experience would invoke sympathy, but not from some.

“It’s not the bank’s fault this woman gave her money to a scammer,” wrote the account identifying as ‘Christine Comments’ on Facebook.

This sort of victim-blaming perspective reminds me of the days when women who were sexually harassed were told they shouldn’t have worn a miniskirt.

Ms Comments does not know the full details of the scam or the extent to which NAB may or may not be culpable for the alleged fraud.

It seems coincidental that the victim received a call from a man claiming to be from the fraud squad, who knew her personal details, so soon after dealing with the bank.

This does not prove any wrongdoing on the part of NAB, but when Region asked the bank if it investigated whether a security failing or leak may have contributed to the alleged scam, it refused to respond.

The big banks have also pushed elderly customers to use unfamiliar technology, reduced human-to-human customer service, and failed to properly educate people on the dangers of online fraud. This has put many customers in a vulnerable position when trying to navigate between apps, bots, the Internet and overseas-staffed call centres. It’s no wonder they may get confused about whom they are speaking to and where a message has come from.

Similarly, Facebook’s parent company, Meta, seems to allow scam profiles to proliferate, often ignoring multiple reports on them and allowing scammers to create new accounts if they are eventually blocked.

Fake butchers seem to be a growing industry. One allegedly scammed a woman out of $250 on a fresh meat delivery that never arrived.

Once again, the victim faced online ridicule for allowing it to happen.

But who among us has never made a mistake or fallen for a lie?

The women who lost money to the ‘butcher’ and fake bank official were both intelligent and articulate, illustrating how pervasive online dangers can be.

There are many of our fellow citizens with dementia or disabilities who are easier prey for unscrupulous predators and deserve more protection from our governments, financial institutions and social media giants.

When we hear about a victim of fraud, the best thing to do is show compassion and point the finger of blame where it really belongs.

Original Article published by Oliver Jacques on Riotact.