Qing Dynasty coins uncovered in Fitzmaurice Street, Wagga Wagga in 2006. Photo: Museum of the Riverina.

From the mid-19th century, Wagga Wagga became home to a growing number of Chinese migrants who established an encampment on Fitzmaurice Street that would eventually become Wagga’s Chinatown.

In the 1860s, wealthy widow Susannah Brown leased a large portion of her riverside land near the Hampden Bridge to members of the Chinese community who were dispersed across the Riverina. They primarily worked as agricultural labourers after their success on the gold fields ran out or prejudice drove them off their diggings.

At its height, the Wagga Chinese encampment housed more than 220 people. Initially, the accommodation consisted of makeshift shanties and suffered from poor sanitation that was exacerbated by the river’s regular flooding.

The unhealthy conditions in the camps and the existence of gambling, prostitution, opium smoking and sly grog prompted an investigation in 1883 conducted by the sub-inspector of NSW Police, Martin Brennan and prominent Sydney businessman and philanthropist Mei Quong Tart.

Quong Tart was a highly respected advocate for Chinese migrants and called on the government to halt the importation of opium, except for medical use, and to introduce better legislation to control gambling.

They reported that most of the sex workers on site did not hail from China but had voluntarily gravitated there from Melbourne and that their clients, as well as the unruly drunks, were mainly European.

They concluded that the Chinese were “the most industrious race in the world” and the vegetables they cultivated in their market gardens were of great benefit to the community.

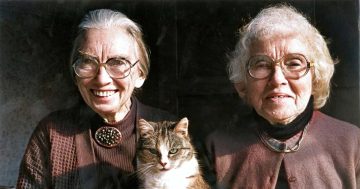

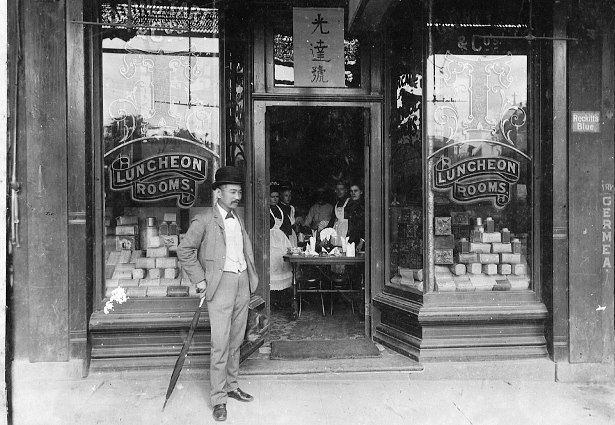

Businessman Quong Tart was a leading figure in early Chinese-Australian relations. Photo: Society of Australian Genealogists.

Over the years, the Chinese introduced pumping and drainage systems to regulate irrigation and more substantial buildings were erected.

Wagga sawmill operators John and James Edney were engaged to build the Joss House, which stood near the old Hampden Bridge at the northern end of the street from the 1880s.

It is described as being constructed of solid Oregon timber, windowless with heavy doors and had spaces for worship and bunks where people could recline to smoke opium.

At some point, the building became known as the ‘Chinese Free Mission Hall’ with a sign erected in both English and Chinese characters.

As some members of the Chinese community converted to Christianity, a church was also built.

Shops and cottages appeared on both sides of Fitzmaurice Street and the area became Wagga’s Chinatown.

Deniliquin’s Chinese market garden in flood. Photo: NSW Migration Heritage Centre.

Prominent among Chinese business owners was Tommy Ah Wah, who owned and managed several businesses in Junee and Wagga. Tommy is credited with founding the first motor garage on the site in the 1920s.

Wagga entrepreneur Alf Ludwig acquired the garage and adjoining sites in the 1940s. Planning to demolish the now abandoned Chinese structures to develop his business, he offered to relocate the Joss House/Mission Hall as a commemorative gesture to a site nominated by Council, however Council declined, so it succumbed to the wreckers.

The Age of 29 September 1939 records that during demolition, workers discovered not only an old iron bell and drum but also 66-year-old man Ah Get. He was blind with long hair and a beard and dressed in rags and had lived there as a recluse for many years.

In 1954, to much fanfare, Alf Ludwig opened his redesigned premises. The Grand Garage was a slick art deco facility offering fuel sales, used cars, a mechanics workshop, a fully equipped kitchen, men’s and women’s showers, a writing room and even a ballroom!

The shell of the church with Chinese writing and motifs still visible on its walls was used as a storeroom but has since gone.

Alf is credited with stories that tunnels had been dug under Fitzmaurice Street supposedly to allow the Chinese to travel between buildings undetected and that a gold statue that went missing from the Joss House may have ended up in the river.

Although these tales have not been substantiated, Qing Dynasty coins were discovered at the northern end of Fitzmaurice Street in 2006.

In 2024 only one part of the Grand Garage still stands and has operated as an automotive service centre under the management of Paul Seaman for the past 40 forty years.

Its distinctive art deco shape has been retained and inside a sprung wooden dance floor and a few fixtures and fittings pay witness to its former glory.