Wounded Australian prisoners of war after the battle of Fromelles in 1916. Photo: AWM (A01551).

At 11 am on 11 November 1918, the guns on the Western Front fell silent after more than four years of brutal warfare and slaughter.

The following year at the instigation of King George V, on the 11th hour on the 11th day of the 11th month, a period of silence was observed in remembrance of the soldiers who died fighting to protect the British Empire.

In Wagga, mayor EE Collins called the community together outside the courthouse to mark the first anniversary of the signing of the armistice “in conformity with the wish of the King”.

Just before the clock struck 11, the city’s fire bell rang out and a hooter was sounded.

The large crowd fell silent for two minutes before Mr FJ Philpott raised a bugle and sounded the Last Post.

In his brief address, Mayor Collins praised the “lads who went overseas that we might live in peace and comfort” and paid tribute to the “gallant dead” and the price paid by their families.

Around 60,000 Australians were killed during the ‘Great War’, another 160,000 were wounded and more than 4000 Australians became prisoners of war.

Well known Wagga skin dealer Herbert Murphy was one of them.

In late 1915, the 34-year-old was compelled to “don the King’s uniform and fight for liberty and freedom” and returned home on a mail train in June 1919, a shadow of his former self.

Pte Murphy was drafted to the military camp at Cootamundra and in December 1915, he was part of the famous Kangaroo March from the Riverina to Sydney.

Murphy and his fellow Kangaroos soon shipped out for training in Egypt before landing at Marseilles in France in June 1916.

The Kangaroo March began in Wagga in December 1915. Photo: AWM.

At the Battle of Poziereshe, Murphy was partly buried when an enemy artillery shell exploded nearby and he spent four months recovering from shell shock in London.

Once back in the trenches, he fought in the Battle of the Somme at Gueudecourt where Anzac troops were left to hold the mud-soaked village and endured some of the filthiest conditions on the Western Front.

On the Hindenburg Line, a hastily planned attack on Bullecourt was scheduled for 10 April 1917 and it was decided that the British 5th Army, including Murphy’s 4th Australian Division, would advance on the German trenches without artillery support – something that had never been attempted.

Instead, it was proposed that a dozen tanks would lead the Australians across no-man’s-land, but when they failed to arrive, the attack was postponed.

The following morning, several of the armoured vehicles were again held up and, as the assault began, others broke down in the cold or were destroyed, leaving just one tank to reach the enemy’s trenches.

Tripping through fields of barbed wire under a hail of bullets and fighting hand to hand in the frozen mud, the Australian infantry achieved the near impossible feat of breaking into the German trenches without artillery cover.

Australian troops in the trenches at Riencourt in May 1917 before the second battle of Bullecourt. Photo: AWM.

Fighting near the village of Riencourt, Murphy was in charge of a Lewis gun and remained at his post despite being wounded in the left leg by shrapnel.

As the Australians found themselves stranded and cut off from reinforcements, the Germans counterattacked and began to encircle the outnumbered Anzacs.

Many of the survivors made a break for their own lines, running back past their own burning tanks to where they had started the day just hours earlier.

Around 3000 Australians were killed or wounded and more than 1100 were taken prisoner, Pte Herbert Murphy among them.

”The treatment we received at first as prisoners was fair, considering the circumstances,” Murphy told a reporter from Wagga’s Daily Advertiser.

The prisoners were soon taken to Dolmar in Germany where they spent the next three months.

“We received good treatment at times, but harsh treatment at other times,” he said, describing the living as “rough” and the food as sloppy, unclean and with little nourishment.

Eventually transferred to East Prussia, the soldiers were put to work on farms where he said the women would spit on them and the guards beat them with their rifle butts.

On one occasion when he failed to respond to an order barked at him in German, a guard twisted his arm behind his back until the bone broke and then threw him forward into a barrel, breaking his left shoulder.

Living on meagre rations and in squalid conditions, Murphy said they would not have survived without regular parcels from the Red Cross.

“God bless the Red Cross, was an oft-repeated prayer of the unfortunate and ill-used prisoners,” he said.

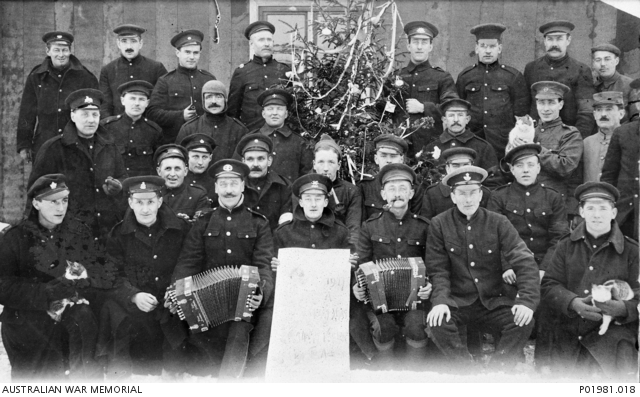

In this postcard sent by Herbert Murphy to the Red Cross we see POWs in black dyed uniforms gathered around a Christmas tree outside their barrack. Murphy is standing in the back row to the right of the Christmas tree. Photo: AWM.

When news of the armistice finally filtered into the camp, he said their treatment improved and over the next six months, the prisoners began to return to Australia.

Still nursing a damaged shoulder and suffering from a “nervous disability” Murphy would make regular trips to Randwick to continue his long road to recovery.

Shrugging off his ailments, Murphy told the reporter, ”I was only one of many who were cruelly treated by the Germans.”