General Sir Thomas Blamey shakes hands with Warrant Officer Class Two J R Reinke, who would die in the aircraft accident the next day, 7 September 1943. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

Warning: The following story contains language/images which may offend/distress some readers.

Incredibly, Australia’s worst air disaster, which claimed the lives of more than 60 infantrymen towards the end of the Second World War remains largely unremembered.

Eighty years ago on 7 September 1943 in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, dozens of men were killed when a fully fuelled US Liberator B-24 Bomber ploughed into a line of trucks loaded with diggers waiting to be airlifted to the front lines.

Survivors were sworn to secrecy to preserve morale and the families of the 62 Australians and 11 Americans who perished were kept in the dark.

At least two of the casualties were Riverina lads and they were commemorated this week along with their comrades at a service at the Anzac Memorial in Hyde Park in Sydney.

“In the blink of an eye, our nation lost 62 men – 60 soldiers of the 2/33rd Battalion as well as two Australian truck drivers,” said Minister for Veterans, David Harris at Thursday’s (7 September) service.

“We pay tribute to the ultimate sacrifice they gave for their country, to keep us safe.

“We also remember the 11 airmen of the United States who also perished during the crash.”

An American heavy bomber (in RAAF service) B-24 Liberator. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

Bill Crooks was a sergeant in the 2/33rd and recalled the morning of the incident in the battalion’s official history, The Footsoldiers.

He was sitting on the tailgate of one of 18 trucks parked at the end of the runway about 4:20 am when they saw the lights of the bomber coming towards them, low to the ground.

“The bomber came crashing through the trees, its engines roaring,” he wrote.

“The left-wing sheared off and the fuselage smashed down like an arrow into the trucks. A great explosion rocked the area and a vast brilliant yellow flash lit everything up brighter than day.

“For a moment only the sounds of falling parts of aircraft and other debris and the crack of flames could be heard. Then, almost together, there broke out the screams and moans of men.”

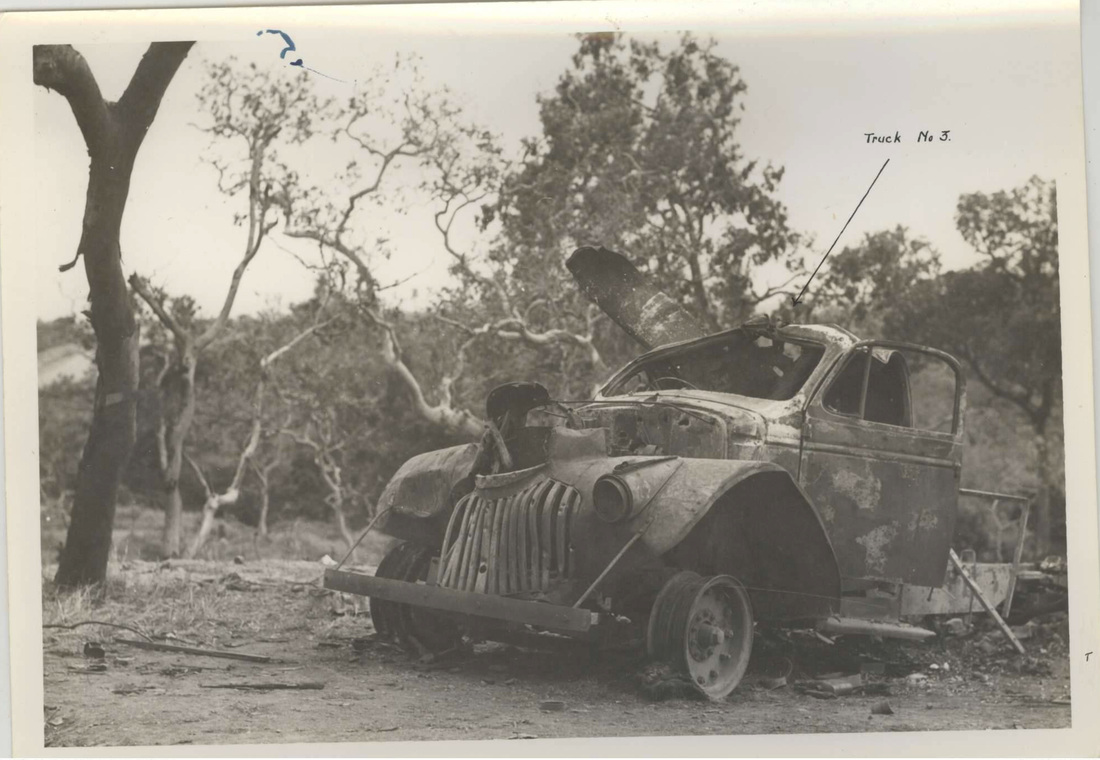

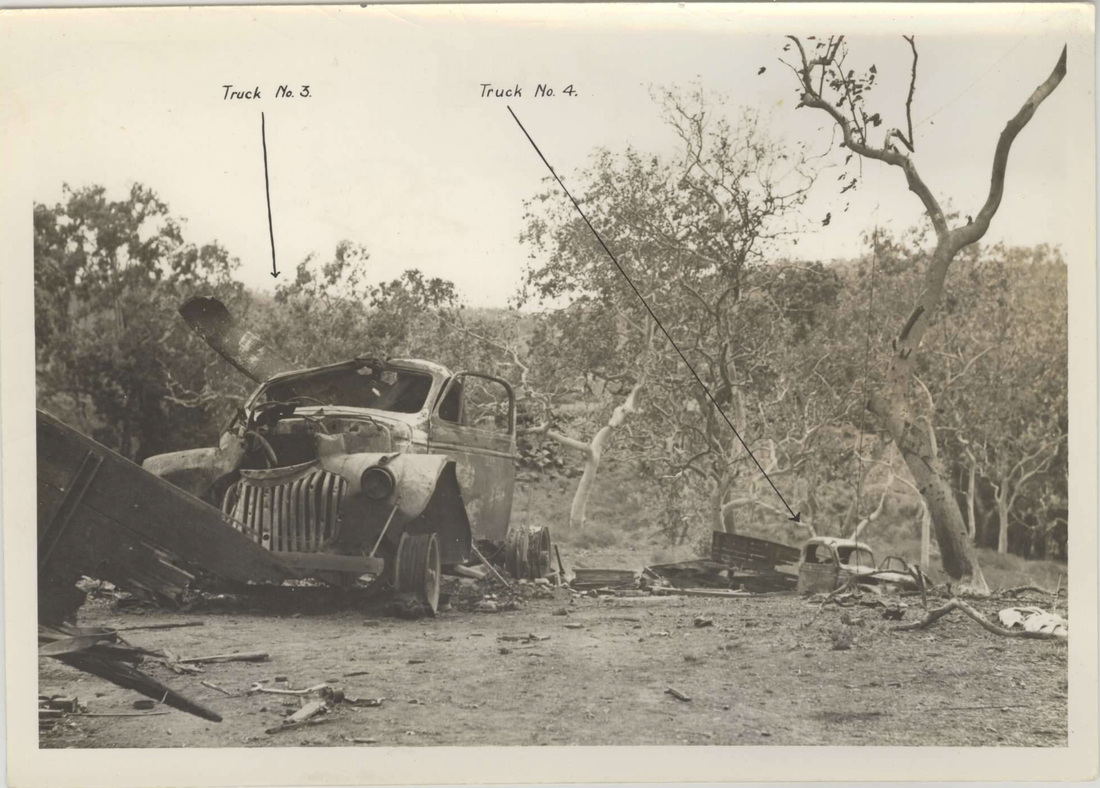

One of the trucks with a propeller hub lodged in the rear of the cabin. Photo: 2/33 Australian Infantry Battalion War Diary.

Two of the Liberator’s four 500-pound bombs exploded on impact and a third went off later in the flames as 2800 gallons of burning petrol poured out across the field.

Crooks had been blown off the truck and found himself hanging in a tree by his belt.

Fire engulfed the trucks and men ran for cover as the diggers’ ammunition began to ignite.

“Men, charging about on fire, would suddenly disappear as either the grenades or two-inch mortar bombs they were carrying in their clothes or equipment, exploded,” Crooks recalled.

“Others, rolling themselves on the ground to put out the flames, would suddenly jerk as their bandoliers exploded.”

In a 1971 account from the Papua New Guinea Post-Courier, Doug Cullen and fellow officer Ray Whitfield recalled a man walking naked from the flames in a pair of smouldering boots.

“Sir, where shall I go?” he asked in an American drawl and died minutes later.

They also found Lieutenant Frank McTaggart with a horrific open wound on the top of his head through which they could “see his brain pulsating”.

Figuring that he would not survive, they made him comfortable propped against a tree, however, in 1971 they reported that he was still “very much alive, with a plate in his head”.

A total of 18 trucks, each loaded with 20 men, were parked at the end of the runway. Photo: 2/33 Australian Infantry Battalion War Diary.

The incident remained top secret under orders from US General Douglas MacArthur, who threatened any soldier who shared news with court-martial.

An army court of inquiry found there was no neglect, misconduct or carelessness associated with the disaster.

In Sydney this week, Mrs Yvonne Unitt, president of the 2/33rd Australian Infantry Battalion AIF Association laid a wreath to honour the association’s fallen comrades.

“Today’s commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the Liberator crash, Australia’s deadliest air disaster, marks another milestone in our association’s important work of honouring and remembering not only the courage, service and sacrifice of our 2/33rd Battalion soldiers,” she said.

“Formed in August 1945, four days after the Americans dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima our association’s work has become even more important because it is one of the few Second World War associations still in existence and has strong support from the relatives of the 3065 men who wore the battalion’s famous red and brown colour patches into battles in the Middle East, Papua New Guinea and Borneo.”

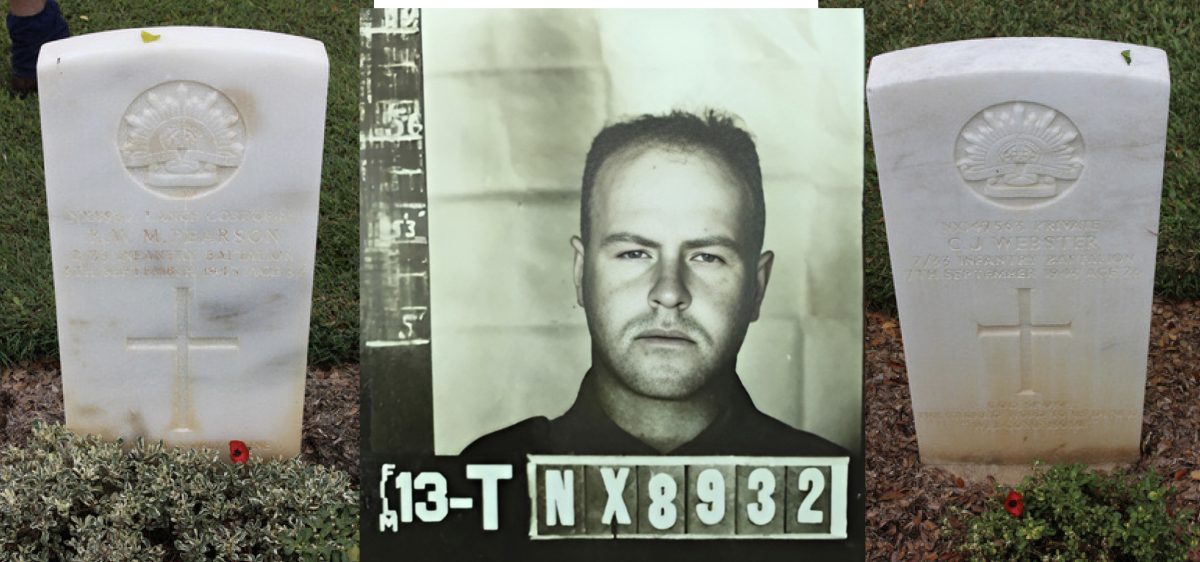

Narrandera’s Rupert Pearson and the graves of both Pearson and Charles Webster from Hilston. Photo: LiberatorCrash.com.

Among the list of casualties, we remember two of our own:

Thirty-two-year-old Rupert William Maitland Pearson was the son of Arthur Gordon and Violet May Pearson of Narrandera.

Twenty-six-year-old Charles James Webster was the son of Arthur Sidney Lindon and Margaret Webster and the husband of Agnes Ray Webster, of Hillston.

Lest We Forget.