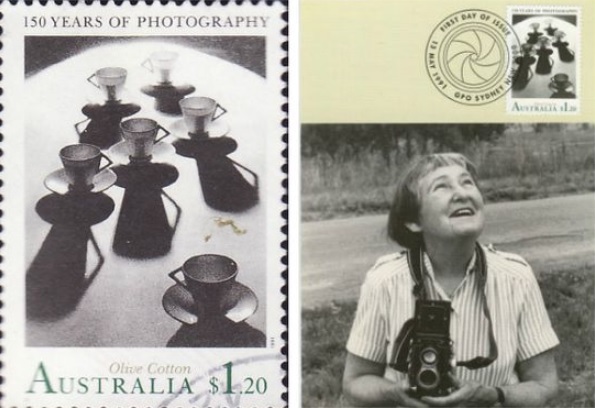

Olive Cotton, holding camera (1937) by Max Dupain. Source: NSW State Library.

Sonia Turner’s first memories of married life in the northern reaches of the NSW Hilltops region were punctuated by walks in the bush with her husband’s aunt.

Often, she says, she’d time her visits so she could join this aunt, then in her 80s, to roam shadowy, treelined roads around Morongla Creek, near Koorawatha.

It was an experience Sonia knew she’d never forget, and hasn’t; aware she was in the presence of someone whose exceptional life had played out in a place and a time so far removed from their footprints in the dust, it seemed implausible.

“Those walks, you know, it was quite wonderful because she was a modest sort of a woman,” Sonia said, “she rarely spoke of her achievements.”

When the photographer Olive Cotton moved to Koorawatha with her husband Ross McInerney in the 1940s, it was as if she’d packed up her old life and left it behind in her hometown of Sydney.

For the most part that life was also confined to the closets of her mind.

“But I remember one particular day we’re walking along and she just started telling me about, you know, the certain times in her life, it might have been in the 30s, and I knew I was hearing something pretty amazing because of the people she knew back then, that bohemian sort of art group,” Sonia said, “it was something she never really talked about.”

“I wish I’d recorded that conversation,” she said, “it offered a remarkable insight into Olive’s life before she moved to the country.”

Olive Cotton was, in fact, one of Australia’s leading 20th century photographers and a pioneer of modernist photography with a career spanning six decades.

But to Sonia Turner, Olive Cotton, aunt and neighbour, was a quiet, gentle, modest woman whose light was obscured by the pristine bushland that was her home, but for her remarkable powers of observation and reflection in those moments where simply walking in nature became her art.

“It was a simple pleasure to walk with her, to share in that and for her to slip in and out of stories and thoughts that to us were just emerging,” Sonia said.

Today Olive Cotton’s story is no secret – bodies of work – stories, books, film, exhibitions – have been dedicated to her life and aspiring photographers vie for the annual Olive Cotton Award for photographic portraiture, one of Australia’s most prestigious photographic awards.

Just last October marked the first voyage of the Olive Cotton, which placed her in a class of her own as a Rivercat-class ferry.

At the time her daughter Sally McInerney, also an eminent photographer, said her mother always loved the sea, despite spending much of her life away from it.

“Many of her photographs were taken at beaches around Sydney during the 1930s and 1940s. When she married and went to live in the country far from the coast, people would ask if she ever missed her city life and professional career, but the only thing she admitted to missing was the sea.

“Olive’s family is sure that she would have been surprised, gently amused and extremely appreciative at being included in the excellent company of the Sydney Ferries fleet.”

Born in Sydney in 1911, Olive Cotton discovered photography in childhood when gifted a Kodak Box Brownie camera, her father setting up a darkroom in the laundry of the family home.

Through school and university – which she graduated with an arts degree in English and mathematics – Olive remained committed to her craft and would work at the studios of her childhood friend Max Dupain, with whom she’d grown up taking photos at Newport Beach.

Dupain, Australia’s most respected and influential black and white photographer of the 20th century; his representation of Australia’s beach culture through The Sunbaker his most iconic work.

Vapour Trail by Olive Cotton. Source: Cowra Regional Art Gallery.

Officially Olive was Dupain’s ‘assistant’ but she also pursued her own work which was exhibited in Australia and also overseas.

According to biographer Helen Ennis, Olive Cotton’s talent was recognised as equal to Max Dupain’s. The photographic work they produced during the 1930s and 40s was extraordinary and distinctively their own.

Together, Ennis said, Olive and Max could have been Australia’s answer to Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, or Ray and Charles Eames.

The pair married in 1939 before eventually divorcing in 1944.

Despite their marital separation, Olive would continue to run Dupain’s gallery through the war years when he served overseas.

In 1944 she married farmer Ross McInerney and in 1946 they moved to Koorawatha, where they had two children, a daughter, Sally, born in 1946, and a son Peter, born in 1948.

They first lived in a tent before moving to a hut that had no running water, electricity or telephone.

Cotton would teach mathematics at Cowra High School from 1959-63, but in 1964 established a small studio in Cowra working professionally on children’s portraits, wedding photography and landscapes.

But Olive had continued to take photographs, her negatives carefully stored in an old sea trunk on their property “Spring Forest” until the 1960s. Now with a darkroom, Olive could devote time to printing from that vast personal archive, the great majority of her subject matter in the natural world rather than the human one.

Olive Cotton’s Teacup Ballet was issued on a stamp to mark the 150th anniversary of Australian photography. Image: Pinterest.

In the early 1980s she resumed exhibiting to critical and public acclaim with her photos included in the 1981 Art Gallery of NSW exhibition ‘Silver and Grey’ and the 1981–1982 touring exhibition ‘Australian Women Photographers 1890-1950′.

In 1983 Olive was awarded a Visual Arts Board grant to print photographs for the retrospective exhibition, ‘Olive Cotton Photographs 1924-1984’, which opened at the Australian Centre for Photography in 1985 and subsequently toured.

In 1991 one of her recognisable shots, Teacup Ballet, taken in 1935, was issued on a stamp to mark the 150th anniversary of photography in Australia.

She was awarded an Emeritus Fellowship from the Australia Council in 1993.

Olive Cotton died in 2003 at the age of 92 and is buried at the small cemetery at Morongla Creek.

Her work is held in numerous public collections around Australia, including the Art Gallery of NSW and the National Portrait Gallery.

Her resurgence 40 years after disappearing from the art scene was no surprise to her family.

As Sally McInerney once told Sonia, “She was never lost to us, but she was more rediscovered by the public.”

Light Years, a documentary by Kathryn Millard, released in 1991, has just been remastered from the original film negatives.

Here a smiling Olive says her “lost” years were never squandered: “I had a job to do raising a family and I could still go on taking photographs, always with the feeling that one day I would have the chance to make prints myself”.

People wishing to learn more about Olive should read Helen Ennis’s book Olive Cotton: A life in Photography (2019).

Original Article published by Edwina Mason on About Regional.