Valerio Ricetti with farmer Gino Pagna at the Ceccato farm in 1943. Photo: Peter Ceccato.

Valerio Ricetti was a reclusive but talented Italian immigrant who built rock shelters and terraced gardens on Griffith’s Scenic Hill, where he lived in isolation between 1929 and 1952.

One aspect of his life often glossed over is his extraordinary run of bad luck with the ladies – notably a barmaid, then a working girl, a jealous farmer’s daughters and even some local skinny dippers.

Ricetti had migrated to South Australia as a 16-year-old in 1914 and lived in Broken Hill before making his way to the Riverina by foot. Remnants of his home continue to stand as one of Australia’s most unusual tourist attractions – Hermit’s cave.

But why on earth would anyone want to live alone in a cave on a hilltop with no water source for more than two decades?

After speaking to Griffith residents who met him and reading a wonderful book on his life by local Peter Ceccato and several articles on him, it seems to me that his life choices were shaped by bad experiences with women.

The barmaid

After securing work in the mines of Broken Hill, Ricetti fell in love with a barmaid named Joyce.

According to Ceccato, the Italian wanted to marry her – he visited her home and gave money to her parents. But Joyce had another lover, an Australian named Rodney. Ricetti seemed to come off second best, telling Ceccato that both Rodney and Joyce would boss him around and physically beat him up. After living in their house as the third wheel, the couple kicked him out, prompting him to return to South Australia.

Those who knew Ricetti said he continued to pine for Joyce decades later while living in his cave, looking to the sky and imagining her there.

Muller’s daughters

After a stint in Adelaide, Ricetti made his way to Red Cliffs near Mildura, where he obtained work and lived with a forest plantation owner known as Mr Muller.

His new boss and landlord was a strict man who had two daughters and gave Ricetti one rule: “I warn you only once and that is now, no nonsense with the girls or I will kill you and bury you in the forest”.

Once again, luck wasn’t on Ricetti’s side. Ceccato wrote that a horrendous storm struck late one night, causing tree splinters to smash through the daughters’ bedroom. The terrified girls barged into his room and insisted that he sleep in the bed between them.

He didn’t want to, but had to oblige, because the girls were “screaming hysterically”. As lightning and thunder struck, Ricetti’s nerves were shredding – not because of the storm but because their father was due home any minute.

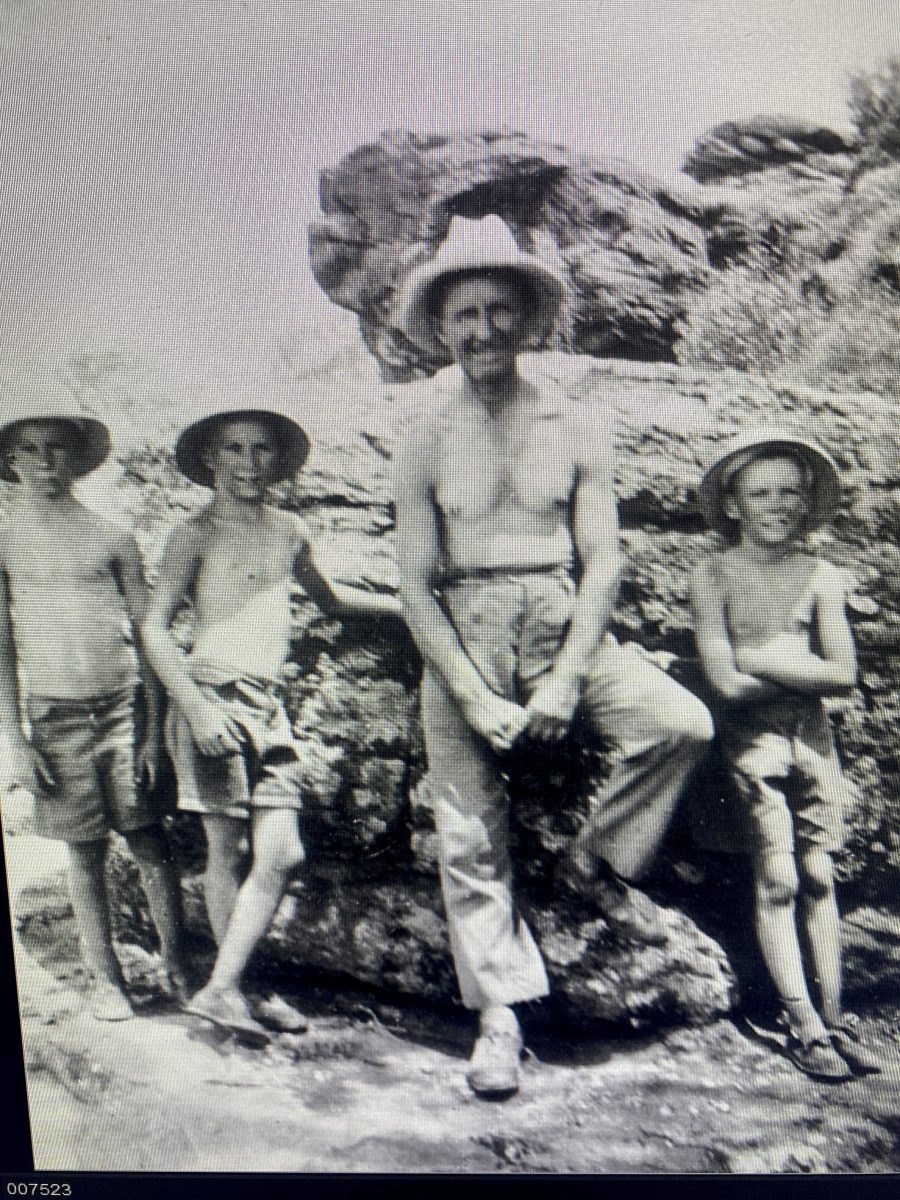

Jim Fielder, Bill Fielder, Valerio Ricetti and Nevill Aspinall outside Hermit’s cave in the summer of 1939. Photo: Griffith and District Pioneers Series 1.

The working girl

Mr Muller didn’t catch Ricetti with his daughters but trouble once again found the Italian soon after during a random night in Adelaide, where he walked past a brothel and an attractive lady lured him inside.

“I paid the fee and put the wallet back in the trousers. After I finished I put my trousers on but the wallet was missing,” Ricetti told Ceccato. An article by Dan Slater in National Geographic said his wallet contained a full year’s wages.

When Ricetti complained, a bouncer roughed him up and threw him out. Ricetti retaliated by throwing a stone at the brothel window. But you guessed it – police officers happened to wander the streets nearby and he was thrown in jail for five days.

Skinny dippers and final chapter

There were plenty more hard luck stories in Ricetti’s life before he made his way to Griffith, fed up with the world and ready for a life of solitude. He did have some human contact though – Peter Ceccato’s father Valentino, brother Bruno and other members of this family supported him, giving him food, work and money.

While Ricetti lived mostly in isolation with no female partner, he somehow couldn’t avoid more problems with the fairer sex. One day, while riding his bike across the main canal, some girls who were swimming in the nude accused him of staring at them and pulled him and his bike into the water.

He continued to live in his Griffith until 1952, when he flew back to Italy to visit his family. He never returned to Australia, dying the same year.

Ricetti’s cave outlasted him and perhaps that’s just as he’d want it: quiet, sturdy and blissfully free of troublesome barmaids, jealous fathers and suspiciously timed skinny-dippers. After all the turmoil, Scenic Hill gave him something rare — a place where life finally stopped chasing him.