Is the Riverina food bowl under threat? Photo: iStock/VeselovaElena.

The Riverina has long been regarded as Australia’s ”food bowl”, feeding the country with the diverse range of fruit, vegetables, meat and dairy grown here.

But it’s not nearly as diverse as it used to be. Over the past 20 years, several food staple producers have left the region, often replaced by corporations that tend to specialise in a narrower range of products such as nuts and cotton.

This trend is no accident, according to water expert Maryanne Slattery of research firm Slattery & Johnson.

“[Government] policy since the 1990s has been to move water to its highest-value use,” she said. “It was an explicit aim of CoAG [Council of Australian Governments] in 1994 to move water to horticulture, away from so-called ‘lower-value uses’ such as rice and broad-acre farming.

“Governments are understandably reluctant to tell farmers what to grow. However, if we want to maintain a dairy and rice industry, we need a water policy that achieves that.

“We risk losing agricultural diversity in regional communities, leading to declining populations in those areas.”

This view is echoed by Mel Gray, who grew up on an irrigated vegetable farm near Grafton and now works as a campaigner for environmental group the Nature Conservation Council.

She believes current tax and policy settings also favour large foreign multinationals over local family farms.

“When the $13 billion for the Murray Darling Basin Plan was announced, that got the attention of international players who knew how to play the system,” she said. “The biggest players have gotten all the money and the subsidies. Often, the big companies also get away without paying much tax.”

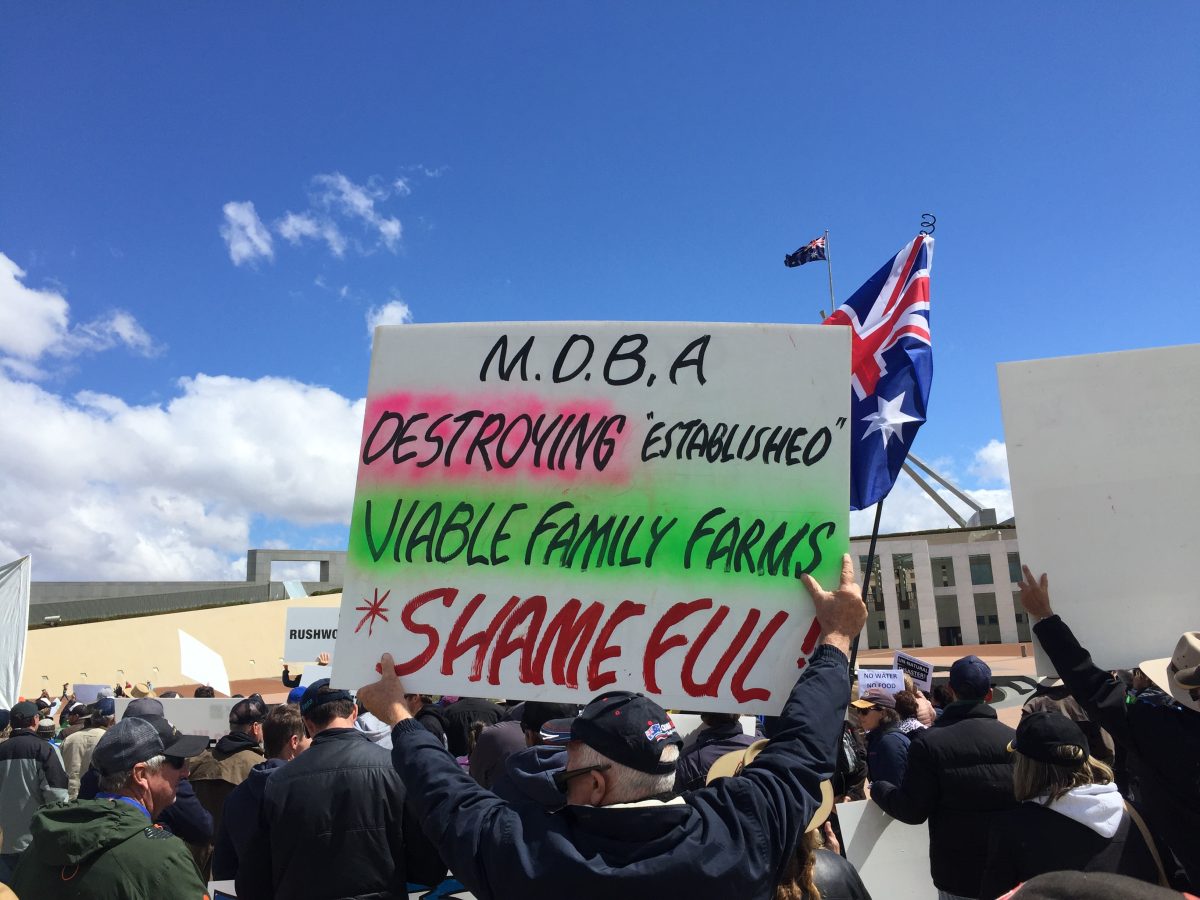

Riverina farmers have often protested against the decline of family farms. Photo: Oliver Jacques.

Foreign corporations are able to avoid paying capital gains tax on profits made from water investments, according to a private ruling by the Australian Tax Office.

Canada’s Stahmann Webster, Singapore-headquartered Olam Group and Italy’s Ferrero Group have set up large nut farms across the Riverina, but there have been signs that fierce competition for scarce water entitlements is heating up.

Last week, Region reported Ferrero Group abandoned its $70m hazelnut farm near Narrandera, meaning it will need to uproot and remove about a million hazelnut trees. Meanwhile, local workers have been left unemployed.

“Foreign corporations have no attachment to the local community,” Ms Gray said. “They’ve got no qualms with just ripping out all their trees and moving to wherever is profitable.”

Nuts are a permanent crop, meaning they need a constant supply of irrigation water every year.

Nut orchards have blossomed across the Riverina as water flows to its highest-value use. Photo: Facebook.

Ms Slattery has long raised concerns about the sustainability of large-scale nut production in the Southern Basin.

“Water supply in dry years is a problem,” she said. “In dry times, there will not be enough water in the river system to support all the nuts that have been planted, as well as provide water to other crops.

“The issue is, which industries will be damaged on the way? There will be fierce competition for limited water. How will the dairy and rice industries manage during the next drought? The 2018-2020 drought provides some pointers.”

Ms Gray says this puts our nation’s food security at risk.

“Food security is a national security issue,” she said. ”Praying to the market gods for financial growth for the wealthiest is tantamount to self-sacrifice. Australia doesn’t have food security as a portfolio – it’s an area where everyone is responsible and nobody is responsible.

“Water and food are so intrinsically linked, it’s far too important to leave to the whims of the market.”

When it comes to nuts, Ms Slattery has questioned whether our governments understand what “highest value” really means.

“The nut industry is not labour intensive. Multinationals who grow nuts are often not creating many jobs and they’re probably not paying much tax, so when we say highest value, highest value for whom?”