Patrick Gaut and his son Finley with the bronze war medallion they discovered buried deep in the backyard of their Tumut home at the weekend. Photo: Danielle Gaut.

A chance find in a Tumut backyard at the weekend has illuminated the wartime service of a young farmer from the district 110 years after he enlisted to fight with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in World War I.

And if Patrick Gaut and his son Finley hadn’t needed to adjust the position of a post for a new carport by just a few inches, the large bronze medallion might well have remained embedded deep in the soil, forever undetected, and the service of Lance Corporal Stanley Walter Murray may have passed unnoticed.

Because you won’t find his name on any local memorials.

Stan “Dooley” Murray was one of 13 surviving children born to James and Catherine Murray of Tumut. His father, James, a farmer, was a native of County Clare in Ireland before he emigrated to Australia with his mother, and Catherine was the daughter of Peter and Mary Kelly of Blowering.

Stan had just turned 20 when in early September 1914, he eagerly travelled to Randwick in Sydney with fellow Tumutians Ernie and Charlie Kershaw to enlist just weeks after Australia committed troops to the war.

The young Stan would have just been finding his feet in life but by October 20, 1914, he and Ernie Kershaw (Charlie having failed his medical) were departing Sydney on HMAT Euripides as privates in the Third Infantry Battalion – one of the first infantry units raised for the AIF during the First World War and part of the 18,000-strong Australian 1st Division.

When Stan wrote home to his father, he told of the sea journey, evidently thriving on board, gaining two stone, while the majority of his fellow soldiers failed to find their sea legs.

After a brief stop in Albany, Western Australia, the battalion proceeded to Egypt, arriving on 2 December, where Stan, among 33,000 soldiers, had a captain by the name of Brooking from Gundagai (who knew his father) and also happened to run into the Elphick brothers of Tumut.

The battalion took part in the Anzac landing on 25 April, 1915, as part of the second and third waves and served there until the evacuation in December.

Of three Tumut men who served in the 3rd Battalion, only Stan would survive.

After the withdrawal from Gallipoli, the First Division troops returned to Egypt and in March 1916, sailed for France and the Western Front, at which point Private Stan Murray was promoted to Lance Corporal.

From then until 1918, they would take part in operations against the German Army, principally in the Somme Valley in France and around Ypres in Belgium.

The battalion’s first major action in France was at Pozieres in the Somme Valley in July 1916, where they endured heavy German bombardment, far surpassing anything yet experienced by an Australian unit, suffering 5285 casualties.

Three weeks later, they returned half-strength to Pozieres Ridge, the 3rd Battalion tasked with taking the Fabek Graben Trench, which ran behind Mouquet Farm, on 18 August.

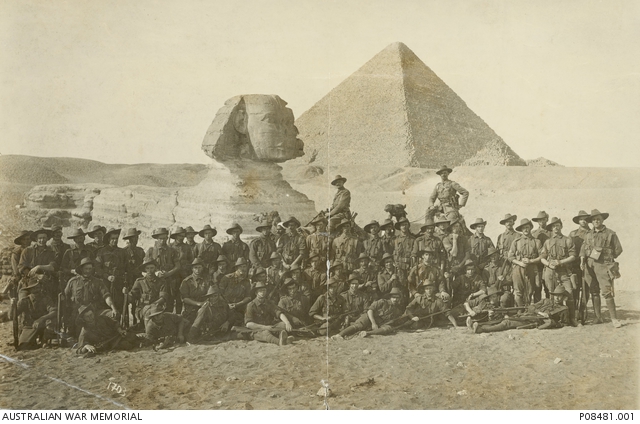

A group portrait of C Company 3rd Battalion in front of the Sphinx and pyramids. This photo is from a collection belonging to Company Sergeant Major Harry Fenton Manning Stead.

In the book titled No Greater Love; Tumut’s Lost Sons of the Great War by the late Colin W Hoad, who used his life savings to honour Tumut’s WW1 heroes, he said confusion about where the front line lay near Mouquet Farm led to the bombardment of the entrenched battalion.

Stan Murray, described by his colonel as a much-liked young man with an amiable and endearing disposition, and a favourite among associations, would die that day.

His body was never recovered, his name instead engraved in stone at the Australian National Memorial Villers-Bretonneux in France and the Australian War Memorial in Canberra but, according to Hoad, for reasons unknown, was not named on any of the local memorials that honour the district’s soldiers.

For long-time locals, it is considered a terrible lingering injustice.

James Murray signed for his son’s medals and awards and remaining possessions including a gift box, metal cigarette case, letters, gloves, testament and an autograph book.

And what lay beneath the caked-on dirt and grime found on Saturday in Tumut was what he would also have received and what Danielle Gaut already knew was a Memorial Plaque, or colloquially, a ”dead man’s penny”.

The 120 mm round bronze Memorial Plaque was issued after WWI to the next of kin of all British Empire service personnel who were killed as a result of the war.

The full name of the dead soldier is engraved on the right-hand side of the plaque, which depicts Britannia and a lion on the front and bears the inscription: “He died for freedom and honour.”

No rank, unit or decorations are shown, befitting the equality of the sacrifice made by all casualties.

The shape and appearance of the plaque, resembling the penny currency, earned it the nickname the “Dead Man’s Penny”, “Death Penny”, and the “Widow’s Penny”.

The great-great-nephew of Stan Murray, Wayne Hibbens, suggests the medallion might well have fallen from the pocket of one of Stan’s siblings, who lived in the house.

He and his mother Helen, Stan’s niece, will be visiting the Gauts to see the “penny” this week.

“I’m just so happy it was found, just now, ahead of Anzac Day,” Wayne said, “I’ve always marched for my great-grandfather Lieutenant Walter Long, who served with the NSW Bushmen’s Militia in the Boer War and Light Horse Brigade during WW1, but from now on I will march with a bit of extra pride knowing a little more about my uncle Stan, who served courageously and survived some of the greatest battles of the First World War before losing his life.”

Danielle Gaut told Region she felt the weekend find was astonishing ahead of Anzac Day: “It was almost like he wanted to be found.”

Original Article published by Edwina Mason on About Regional.