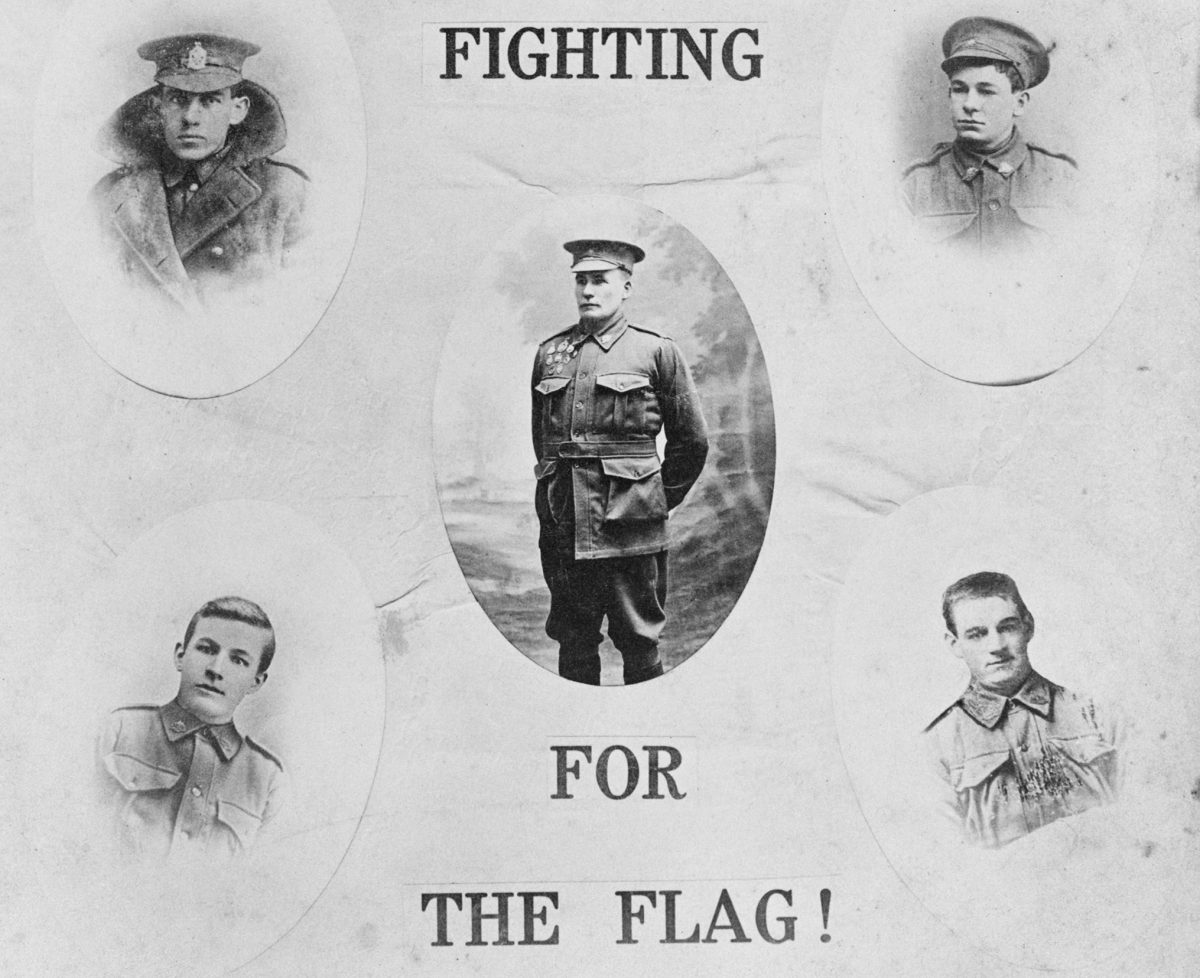

A photo montage of the five men from West Wyalong’s Crowley family who enlisted to serve in the First World War. Image: Australian War Memorial.

Next Tuesday (14 January) at 4:30 pm a bugle’s mournful notes will echo through the Australian War Memorial’s Commemorative Courtyard in honour of a young soldier from West Wyalong whose story comes within striking distance of that Hollywood epic Saving Private Ryan.

Private Reginald Baden Crowley probably should have been rescued from the front during the First World War and it would seem his father pulled out all the stops to ensure his youngest son would survive the war.

A photo montage of five members of the Crowley family held by the Australian War Memorial tells part of the tragic story.

In 1916, the call to serve would have been a powerful pull for young Reggie, whose brothers John Nicholas Junior and Oswald “Ossie” James were already entrenched on the Western Front; John was a sergeant in the King Edward’s 1st Horse cavalry regiment, while Ossie served with the Australian Infantry Force.

The three boys had already lost their paternal uncle Matthew Crowley, who died of the wounds he sustained at Dead Man’s Ridge, Gallipoli on 2 May 1915.

Ossie enlisted by the end of that month, while John enlisted in British Army’s colonial brigade eight months later on 17 January 1916.

Reggie was hot on the heels of his brothers, and according to newspaper records, persistent appeals to his father for consent paid off, because he signed up on May 1916, lying about his age, at the tender age of 16. His enlistment papers had him at 5 foot four and ¾ inches tall.

Informal portrait of Private Reginald Baden Crowley of West Wyalong, NSW. He is wearing a sheepskin jerkin over his uniform and smoking a cigarette. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

As Reggie headed off for England in October 1916, he would be followed, seven weeks later, by his 50-year-old widower father John Nicholas Crowley senior, who had understated his age by six years when he enlisted.

Mr Crowley was a highly regarded West Wyalong local; a journalist, editor and owner of the Wyalong Star newspaper, justice of the peace, district coroner and NSW Southern District rifle shooting champion to boot and would not idly stand by while his sons went to war.

After two years apart, the father and his three sons would reunite in London in January 1917, as recorded in the Sydney Evening News by correspondent HN Southwell, by which stage young Reginald, “a strapping, pleasant youth whose official age did not tally with his real years” had transferred to the same battalion as his father, the 34th Battalion.

John Crowley senior’s death after being hit by a shell in the appalling waterlogged conditions at Passchendaele on 12 October 1917, marked the second tragic sacrifice in the Crowley family.

Ironically, at that time, Reggie was laid up in hospital in England, having been sent to Birmingham to recover from trench fever.

Listed initially as missing, newspaper reports recalled Mr Crowley senior’s stirring speech at a 1916 Country Press Conference “that if the referendum proposals, which were then before the people [a vote on whether to force men to enlist in the Australian armed forces to fight in World War I], were not carried, he would never return to Australia, and preferred that the bones of himself and his three sons to remain in France”.

The month he died he was re-elected onto the executive of the Country Press Association. But he would never see that cable.

Back in the muddy trenches of France by January 1918, Reggie’s mettle was soon also tested.

On 4 April 1918, during a ferocious predawn engagement near Villers-Bretonneux, he was shot twice at close range by a German officer’s revolver. Reggie was just 18 years old.

The two remaining Crowleys – “Ossie” and John Nicholas – would survive the war.

Ossie, who sustained injuries at Gallipoli and Pozieres, returned to Australia in March 1919.

He died in 1978.

John Nichols Crowley was repatriated the same year. He died in 1950.

Reggie Crowley has no known grave but is commemorated in Australian National Memorial, Villers Bretonneux, France and at war memorials across the Bland Shire as well as the National War Memorial in Canberra.

His story will be brought to life once more during the Australian War Memorial’s Last Post Ceremony at 4:30 pm on Tuesday 14 January.

The ceremony begins with the Australian national anthem followed by the piper’s lament.

Visitors are invited to lay wreaths and floral tributes beside the Pool of Reflection.

The individual soldier’s story is told, and the Ode is recited by Australian Defence Force personnel before the ceremony ends with the sounding of the Last Post.

Next month a similar ceremony will be held in honour of Reggie’s father John Nicholas Crowley senior, who is buried in Tyne Cot Cemetery Passchendale and also commemorated at memorials in the Bland Shire, as well as the Australian War Memorial.

He is to be honoured with a Last Post Ceremony at the Australian War Memorial on 19 February.

Original Article published by Edwina Mason on About Regional.