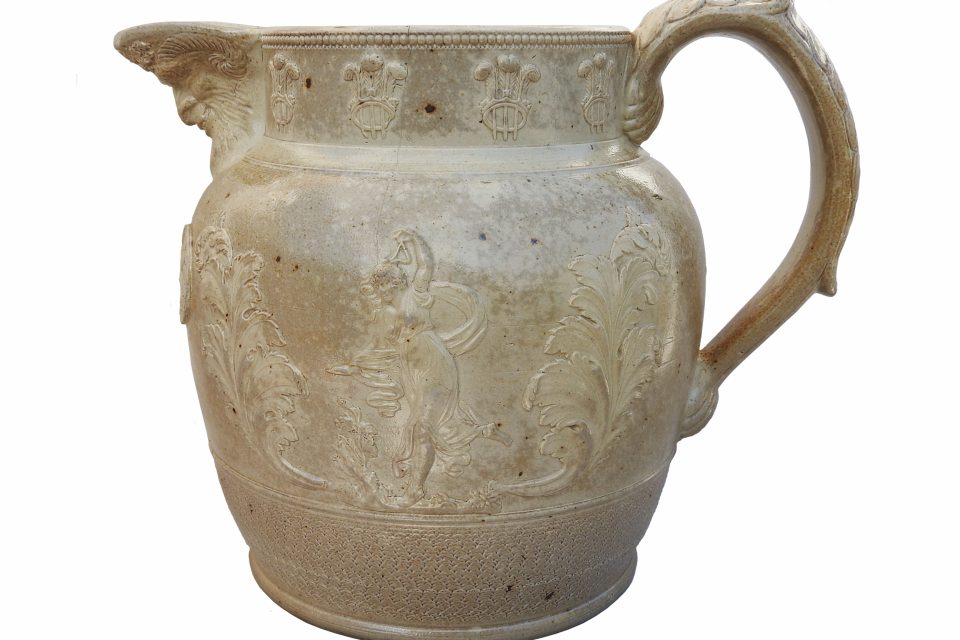

Geoff and Kerrie Ford with the unique and historically significant artefact crafted by the convict potter Jonathan Leak. Now on display at their pottery museum in Holbrook, it offers a glimpse into Australia’s colonial past, shedding light on Leak who was known for his craftsmanship and is considered a pioneer of Australian pottery. Photo: Vanessa Hayden.

There’s no more exciting time as a serious collector than when you find a particularly significant piece to add to your collection.

This is the case for Geoff and Kerrie Ford from the National Museum of Australian Pottery in Holbrook who had “a bit of an anxious month” in the buildup to acquiring Australia’s most important piece of early marked convict pottery ever discovered.

“This is the most elaborately decorative piece of marked convict pottery ever found and we are very, very excited to unveil it here at our museum,” said Geoff.

“It’s an incredibly important 200-year-old artefact made by the convict potter Jonathan Leak, whose few surviving pieces are the earliest pottery produced in Australia marked with a potter’s stamp.”

The Jonathan Leak 1823 Victory Commemorative Wine Jug is a large wheel thrown and salt glazed piece adorned with fine coggle decorations, Prince of Wales plumes, a press-moulded handle and a spout featuring a facemask of Bacchus (The God of Wine).

The 19.5-cm-high jug features both sides of an ‘Arthur Duke of Wellingtonʼ medallion, struck in 1820 to commemorate the victory at the battle of Vittoria in June 1813, against the French during the Napoleonic Wars.

“The medal is believed to have been brought to Australia in December 1821 by Sir Thomas Brisbane, the sixth Governor of NSW, who took part in the battle, and may have had Jonathan Leak commissioned to produce the jug in early 1823 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the victory,” said Geoff.

The hope and anticipation of acquiring the artefact has been a long time coming for the Fords who were first aware of the item more than a decade ago.

The jug had originally been under the ownership of Tasmanian collectors Mr and Mrs Triffet since the 1930s. The pair had a deep interest in military artefacts and had built up a diverse collection including furniture, artworks, numismatics, glass, porcelain and pottery.

Following the couple’s passing in the 1980s, the bulk of the collection was dispersed and the residue, including the Leak jug, was packed away.

“When they passed away the jug ended up in a cardboard box; no-one really wanted it at the time and before that, in the 1930s, it would not have been considered such a significant item,” said Kerrie.

Initially mistaken as British manufacture from one of the Staffordshire potteries, with an obscure maker’s mark, ‘J. LEAK’ impressed on the base, it was among a variety of early English and European pieces from the Triffets’ collection that they exhibited alongside a number of other prominent Tasmanian collectors who all lent treasured items for display at an Antique and Historical Exhibition held in the Hobart City Hall in June 1945, in aid of the Red Cross Society.

In 1996 the Triffets’ son gave the box to a friend who nearly two decades later unpacked it, found the Leak jug, researched it on the internet and was amazed by what he found.

The pottery museum in Holbrook already houses the best collection of convict pottery you will ever see, including an earthenware wine cooler made by fellow convict potter John Moreton; until now the single most important piece of pottery in their entire collection.

“Well, that was up until we received this jug,” said Geoff.

“We had a bit of an anxious month when we knew this jug was available, because we knew how significant it was historically and the importance of the piece. We had really no idea if other institutions or museums or private collectors were going to be interested in it as well.

“After becoming the winning bidders, we collapsed first,” laughed Kerrie, “and after we calmed down there were definitely a couple of hugs and a great sense of jubilation; we were both very pleased with the acquisition.”

Geoff and Kerrie Ford’s pottery collection spans 2050 pieces, 132 potters represented and is spread over two floors containing 125 metres of two-metre-high displays. Photo: Vanessa Hayden.

The meticulous researchers and published authors have become pundits on Australian pottery since their obsession first began in the 1970s and they have come to know Leak well.

Jonathan Leak (1777-1838), a trained Staffordshire potter, had success in business until around 1810 when working conditions coupled with the depression at this period meant profit was meagre. Leak had tried to sell the pottery works without success several times and in 1818 abandoned it and went to work in partnership with fellow potter John Moreton.

Moreton’s younger brother Anson had a relationship at the time with a servant in Mrs Mary Chatterley’s home, Shelton Hall, and on a visit had seen a significant display of wealth, including a variety of silver items.

While Moreton, his apprentice and Leak were standing outside Moreton’s pottery, a chance encounter with travelling jewellery peddlers saw Moreton enquire if they would buy old silver and a price of 5 shillings an ounce was agreed on.

Moreton then asked them to return in a few days and later that day they broke into Shelton Hall. They stole 18 silver knives and forks, five silver tablespoons, 10 silver plates, candlesticks, a coffee pot, a silver crown piece, upwards of 100 pounds in cash notes, some linen, aprons and four handkerchiefs.

During the robbery they spent a considerable amount of time in the kitchen consuming the contents of several wine decanters and bottles of spirits and helped themselves to food from the pantry.

A few days later the travelling peddlers were shown the silver and agreed on a price. They said they would get the money and return the next day. Instead, after seeing a hand-bill regarding the robbery, they reported the trio to the police and all three were arrested. The silverware was found hidden under broken saggars and rubbish at Moreton’s pottery and the handkerchiefs belonging to Mrs Chatterley were found at Leak’s house.

Leak and Moreton were both tried and convicted of burglary in March 1819. Two weeks later their death sentence was commuted to transportation to Australia for life. On arrival in December 1819, they were put to work at the Government Pottery on Brickfield Hill, Sydney.

In December 1821, they were permitted to start working for themselves; Moreton took over the running of the Government Pottery and Leak began establishing his own pottery works on land off Elizabeth Street, near the Brickfields.

By July 1823, after 19 months’ hard work, part of which was producing this jug, Leak had proven the worth of his pottery business and obtained a land grant on his chosen site off Elizabeth Street.

In 1828 Leak received a conditional pardon and by 1833, with the help of his wife, their children, and 20 free men, Leak’s Pottery was producing a range of lead glazed domestic earthenware and salt glazed stoneware bottles, jars, jugs, tiles, bricks, and smoking pipes. Leak’s pottery business continued to do well but came to a halt soon after his death in December 1838.

Plan your visit by checking out the National Museum of Australian Pottery.