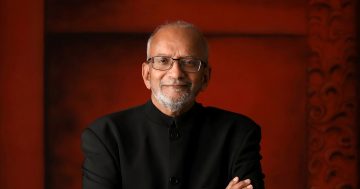

Dr Narayanan Jayachandran revealed the real reason why we don’t have broken bones services in Griffith. Photo: Denny Fachin/What’s On Griffith.

Doctors don’t want to move to the Riverina. And they certainly don’t want to stay.

That’s what authorities tell us whenever we ask why patients in Griffith, Leeton and surrounding towns are expected to travel hours for hospital treatment. Why broken bones, scans and specialist care so often come with a long drive and a full tank of fuel.

It’s a neat explanation: no professional would want to move to Cootamundra when they could be living in Coogee.

If doctors simply refuse to come here, then we can’t blame those in charge for the failings of our health system, right?

But spend any time talking to medical professionals who have moved here, left, or tried to come but couldn’t, and a very different picture emerges. The problem isn’t the Riverina. We’ve been sold a convenient lie.

It’s an excuse that suits the Murrumbidgee Local Health District, which has little appetite for confronting its own management and workplace problems — problems that have produced staff turnover rates that would make McDonald’s blush. And it suits the NSW Government, for whom it is cheaper and more convenient to centralise services in larger centres than to properly resource small rural hospitals.

For the past decade working in media and politics, I’ve heard the same lines rolled out again and again to explain hospital staffing shortfalls. It’s too hard to recruit. Doctors don’t want to live here because they can’t get good coffee. They can’t find decent schools for their children. Their partners have nowhere to shop.

Apparently, this is why a Griffith resident who limps into our emergency ward with a fracture is routinely told to drive two hours to Wagga.

But that explanation doesn’t survive scrutiny. Veteran surgeon Dr Narayanan Jayachandran has said orthopaedic surgeons have wanted to come to Griffith on multiple occasions over the past two decades. They weren’t scared off by regional life. They were blocked — repeatedly — by a Wagga‑centric system that has long treated Griffith as an afterthought rather than a base hospital serving more than 80,000 people.

This helps explain why anger in the community has continued to grow over the lack of orthopaedics, rehabilitation beds and an MRI machine at Griffith Hospital. It also explains why local doctors have publicly backed calls to split hospital governance from Wagga, arguing that decisions made hundreds of kilometres away have actively undermined patient care.

And it’s worth challenging another assumption while we’re at it — that professionals don’t want to live in small towns.

Sure, Sydney and Melbourne offer attractions and opportunities we can’t match. But regional Australia brings advantages that a crowded metropolis increasingly struggles to offer.

Since COVID, there has been a sustained shift of people moving out of major cities. Professionals are drawn by a slower pace of life, less traffic, more affordable housing and the chance to actually see their families. Doctors are no exception. In Griffith, many hospital administrators and clinicians have relocated here, bought homes, enrolled their children in local schools and put down real roots.

Yet many of them don’t last.

Often within a year or two, they quietly head back to their home cities. Not because they dislike the town, but because of frustration with management, bureaucracy and a system that seems incapable of listening to the people on the ground.

They rarely speak publicly, for obvious reasons. NSW Health is not known for rewarding honesty. But the stories are remarkably consistent. Nurses apply for jobs and give up after recruitment drags on for six months or more. Doctors find themselves excluded from decisions that directly affect their ability to do their jobs. Problems are ignored until they become crises.

Griffith Base Hospital has cycled through managers and specialists at an alarming rate — at one point welcoming its sixth general manager in just four years. And the local health district itself has been the subject of investigations into allegations ranging from racism to directing staff to commit unlawful acts.

This is not a failure of geography. It is a failure of governance.

Regional communities are repeatedly told to be grateful for what they have, to accept a level of healthcare that Sydneysiders would never tolerate. We are told the Riverina is unlucky — too small, too far away, too difficult to service properly.

But the evidence points in one clear direction. Doctors are willing to come. Patients are willing to stay. What isn’t working is a system that prioritises control and centralisation over care.

Doctors don’t hate the Riverina.

They’re being driven out — not by the town, but by health leaders and bureaucrats who refuses to admit where the real problem lies.