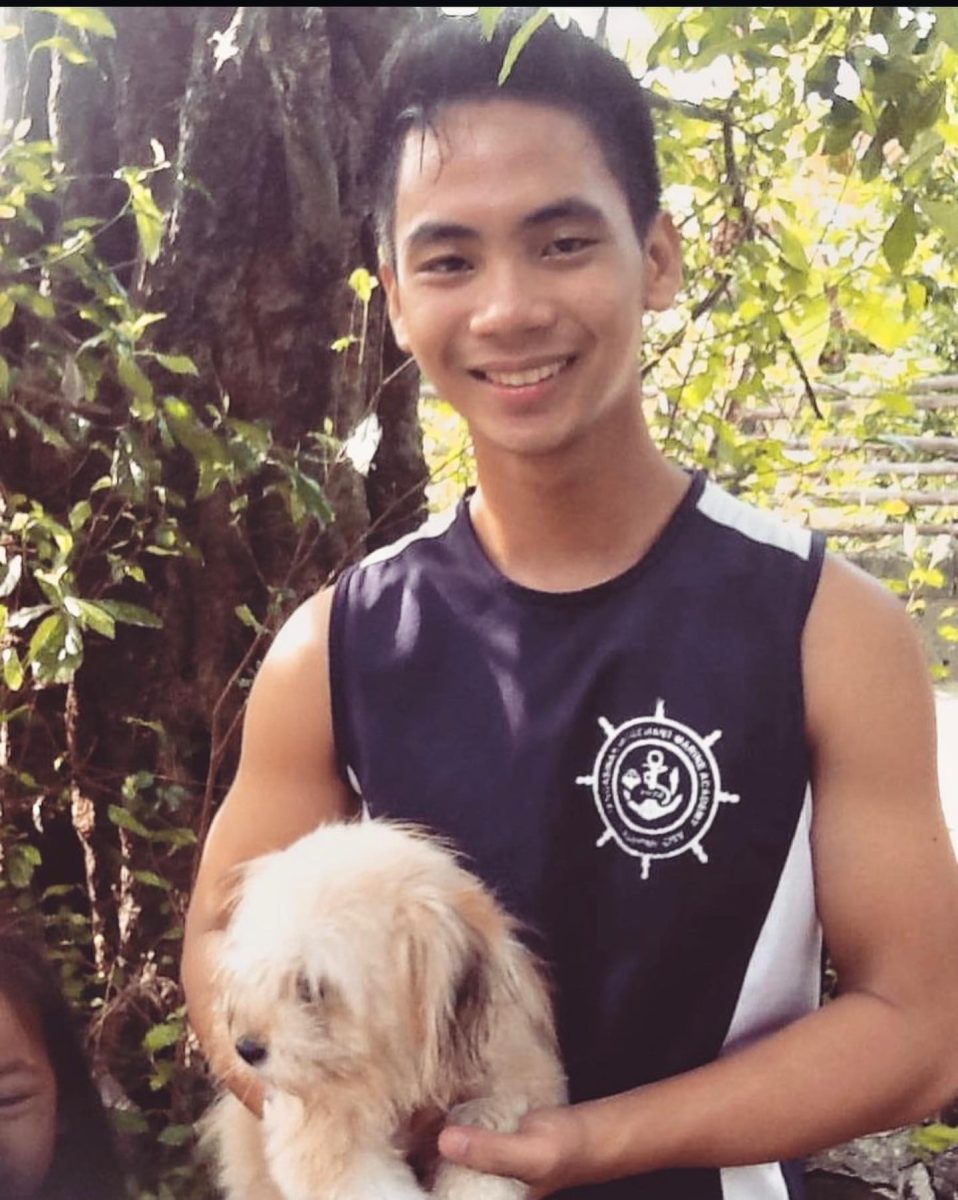

Jessa was very close to her brother Jerwin and now seeks answers on his death. Photo: Supplied.

When Jessa Joy Royupa learned her baby brother was moving from the Philippines to the Riverina for agricultural “training”, she felt reassured.

“I always thought, it was in Australia, so what could go wrong?” she said.

“Even after Jerwin felt fearful, we thought he could never get hurt in Australia.”

Jerwin Royupa is now dead.

In March 2019, the 21-year-old jumped from a moving van and died. Coronial inquest findings handed down last week found he was fearful of his employer, a Riverina winery that exploited him while he was in Australia on a federal training visa. The winery cannot be named for legal reasons.

The inquest was highly critical of the federal Department of Home Affairs (DHA), which approved Jerwin’s visa but failed to adequately check on his welfare or monitor his placement.

Jessa, a 38-year-old Philippines-based lawyer, has travelled to Australia seeking answers about why her “hardworking and caring” youngest sibling ended up isolated, unpaid and terrified — and why no government authority intervened.

“It didn’t seem as if DHA did any checks on his employer before Jerwin’s placement,” she said.

“DHA did no monitoring at all during his placement. Nobody even came by to ask, ‘Are you still alive?’”

Jerwin was known for his love of his church and agriculture. Photo: Supplied.

Training visas allow employers to bring overseas workers to Australia without them paying wages, so long as structured education and skills training are provided. More than 24,000 of these visas have been granted since the program was launched in 2016.

According to evidence before the coroner, Jerwin received no training at all.

Instead, he told his family he was made to perform the hardest manual labour for up to 10 hours a day, six days a week, without pay.

“Filipinos are very hard workers. They don’t like to complain about work, about being homesick or anything,” Jessa said.

“The trigger point came a month into his placement. He wanted to send money back home to his parents to help his family. But he didn’t get a cent.

“The training visa operates like a visa for slaves when there is no monitoring.”

Jerwin was stranded on an isolated farm with no car, limited internet access and English as his second language. He said his passport had been confiscated and he had no understanding of his rights.

“There was nowhere he could go to find out about his rights,” Jessa said.

Jessa thought Jerwin would be safe in Australia.

Coroner Rebecca Hosking noted that the DHA does not even list a phone number on its website landing page — a failure that still has not been addressed.

Jerwin and his friends did attempt to seek help. One contacted the Fair Work Ombudsman, Australia’s workplace regulator.

“They gave her a reference number, said they’d call back but never did,” Jessa said.

Jessa has been supported by Catholic charity Domus 8.7 in her pursuit of accountability.

Domus 8.7 lived experience advisor Moe Turaga, who was himself exploited as a migrant worker, said the inquest exposed a systemic failure by the Federal Government.

“The coroner’s findings reveal the failure of the Department of Home Affairs to perform basic due diligence checks on a visa sponsor, which put Jerwin in a situation where he was isolated, afraid and didn’t know who to call for help,” he said.

“The tragedy of Jerwin’s death needs to be a turning point. Government agencies dealing with migrant workers must learn the lessons of this inquest.”

Despite the coroner’s damning findings, Jessa said her family had received no apology, explanation or contact from the Department of Home Affairs.

“We are still waiting for them to reach out,” she said.

Jerwin Royupa died in 2019. Photo: Migrante International Facebook.

Region asked DHA why it failed to monitor Jerwin’s placement, whether it had contacted the family following the inquest, and whether any changes would be made as a result. The department did not respond.

The Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) was also asked why no follow-up occurred after Jerwin sought help.

“The FWO will consider the coroner’s report when it is available. It is not appropriate for us to comment further,” a spokesperson said.

The spokesperson added that the FWO does not tolerate the exploitation of any worker.

Jessa said her family was now hoping for meaningful reform in a country they believed would protect the vulnerable.

“We want to see changes because we don’t want another life wasted,” she said.